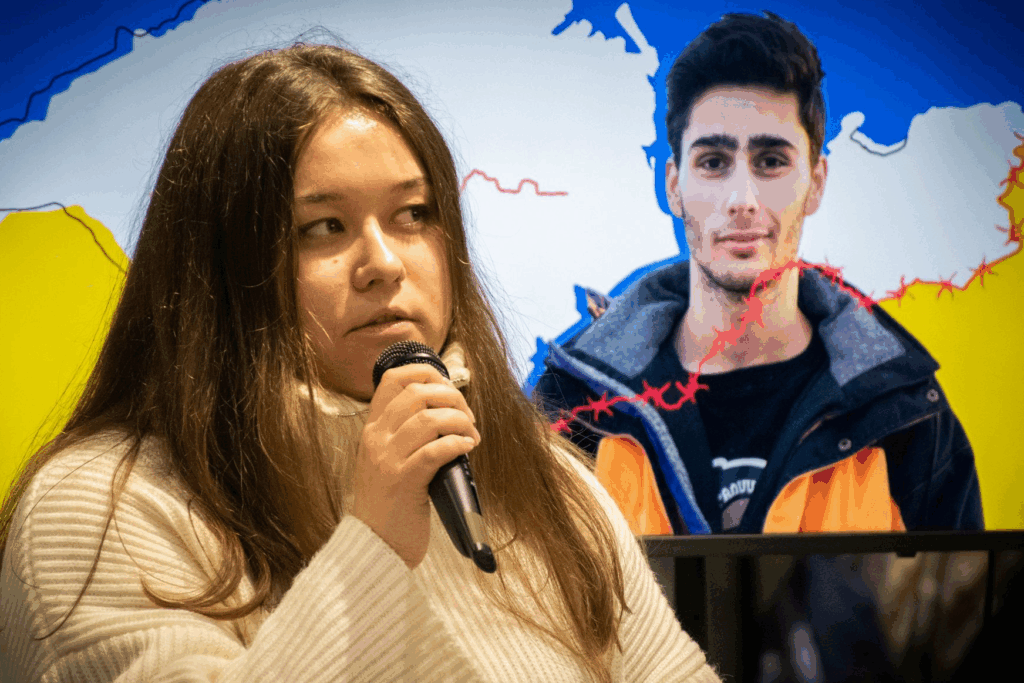

Art that became a crime: the story of Bohdan Ziza through the eyes of a loved one

24 / 10 / 2025

When the world saw russia’s atrocities in Bucha, artist Bohdan Ziza from Yevpatoria responded the best he could — with art. He doused the walls of the occupation administration with blue and yellow paint, turning the protest into a symbol of resistance.

Bohdan paid a high price for this act of courage — 15 years in prison. After all, for the russian system, any manifestation of freedom is a crime. And anyone who dares to resist receives the same response: repression, torture, and inhuman sentences.

However, his voice did not fall silent, and today Bohdan Ziza’s resistance sounds even louder. His sister, Oleksandra Barkova, continued his work, and later others joined her. In an interview for CrimeaSOS, Oleksandra shared her brother’s story, the pain she has experienced over the years, and the unbreakable strength that still holds her together.

“I realized that I had to fight for Bohdan as for my family”

In the media, you are often called Bohdan Ziza’s sister, even though you are from different regions — you are from Zaporizhzhia, and he is from Crimea. How did you meet and what brought you together?

The story of Bohdan is probably known to all of Ukraine. He is an orphan. And, in general, he has been alone all his life.

His creative pseudonym – “Orphan” – very accurately reflects his fate.

We first met when I was nine years old. My parents and I first came to visit our grandparents in Crimea. Bohdan was eleven. We became friends fast. Bohdan is my grandfather’s grandson on his stepfather’s line, meaning there is no direct blood relationship between us, but from the very beginning we felt like family.

He was always very lonely. His mother was not gentle with him, she lacked maternal tenderness. Bohdan went through a lot because of this. Eventually, his grandmother took him in, and his mother died soon after.

My mother was also very attached to him, she even wanted to adopt him, but it didn’t work out then. So, our relationship with Bohdan was formed from childhood, like that of brother and sister.

Bohdan is a person who always gave of himself to others. He knew how to support and warm people with his words. I felt this family connection constantly. And when he was imprisoned, I didn’t even have to invent anything: I just said that he was my brother. Because that’s how it was, in essence.

And then I realized that I had to fight for him as for my family. Because now he has almost no one left: his grandmother stayed in Crimea, his grandfather is gone, and on the Ukrainian side, it’s just us. It’s very difficult.

He practically grew up alone. Later he went to school, and to some extent he was raised by the streets. But at the same time, I probably don’t know a more well-mannered, sensitive, and educated person than Bohdan. He himself has come a long way — he grew up and formed despite circumstances that could break anyone.

How often did you see Bohdan?

We came to Crimea once a year, sometimes once every other year. We didn’t travel there anymore after 2012. Since then, we’ve mostly communicated online.

Bohdan also visited Ukraine several times. But after 2014, he decided to stay home, in Crimea, primarily because of his grandmother, to take care of her. So, our meetings became less and less frequent.

“Over time, his struggle became greater — not only for himself, but also for other political prisoners”

Today, you have literally become your brother’s voice: you actively talk about him on social media, participate in international and national events where you talk about the conditions he is in, and read his letters. What goal do you pursue and how do you feel when you talk about it?

Photo: Mykola Myrnyi/ZMINA

Photo: Mykola Myrnyi/ZMINA

The goal is simple – we really need publicity. It is the only thing that really helps. I’m not talking about big things like exchanges or releases right now, because there are so many factors that influence that. But publicity is what can keep a political prisoner safe. And it really works.

The more we talk about our political prisoners here – specifically and by name – the more protected they are there. Not because russia suddenly starts listening – no, they don’t care. But there are certain red lines: when a case becomes internationally publicized, when foreign partners or human rights organizations talk about a specific person, it creates a certain pressure. They understand that it is better not to touch this person. Because any violence or torture can cause an international scandal. And even if they “don’t care,” it deters torture on their part.

I didn’t realize it right away. At first, we had a fear of causing harm by speaking up. We were afraid to say anything unnecessary, lest our words be perceived as Bohdan’s own position. After all, in russia there are cases when political prisoners are given new terms simply for something said from the outside. So, we chose every word.

I remember when we were still able to correspond with Bohdan (when he was in the Simferopol pre-trial detention centre), he was very surprised that so many people were fighting for him. It seemed unreal to him. Perhaps because of his experience as an orphan, he had become accustomed to always being alone. And he wrote to me: “Well, it’s so active now, but everything will calm down eventually.” He was sure that because of the war, other tragedies, exchanges, and information flows, his story would be forgotten.

And my goal now is to do everything to prevent this from happening. So that he is not forgotten. Because this is important not only for him, but also for every political prisoner.

It is because we do not let this voice go silent that Bohdan has the strength to hold on, to go through all the trials, and even to support others. After all, over time, his struggle became greater — not only for himself, but also for other political prisoners.

It was important for him to show that Crimea is Ukraine. And in prison he saw how many of his like-minded people ended up there because of their resistance. He began corresponding with them, to support them. And now in every letter he mentions their names, asking to pay attention to them.

He recently wrote to me that it would be difficult for him to accept if they released him first, rather than those who were in a worse condition – women, people with serious illnesses. This is very much about him.

So, when I talk about him, read his letters, speak, I’m not just telling my brother’s story. I’m continuing his stuggle. And as long as his story is told, he does not disappear – he lives, and this gives him the strength to hold on.

“There is so little publicity about many political prisoners from Crimea – their loved ones simply don’t have the opportunity to speak”

There are many cases when FSB officers try to intimidate relatives of political prisoners, threatening to worsen the conditions of detention if they make public statements or go public. Have you personally faced such pressure or threats?

Fortunately, no, that wasn’t the case.

However, there were situations that made me wary. For example, when our acquaintances were leaving my native village in the Melitopol area, they were interrogated at the border between the Kherson region and Crimea. Officers tried to find out how these people knew me, who I was to them. That is, the FSB understands well who I am and what I do, they know that I am publicly fighting for Bohdan. But, thank God, this has not yet turned into direct pressure.

Photo: Anzhelika Brushnevska

Photo: Anzhelika Brushnevska

Honestly, I don’t know how I would react if this situation happened. It’s a very difficult question. It’s probably easier for me because I’m in Ukraine, so I can speak openly and I’m not afraid that Bohdan will feel worse for it.

Maybe that’s why I can afford not to be silent. Because I understand why it’s harder for many other relatives. Especially Crimeans. Most of them remain in Crimea – close to their families, so they can visit them in prison. They can’t just abandon everything and leave. And that’s completely understandable, it’s a human decision.

However, that’s precisely why there is so little publicity about many political prisoners from Crimea – their loved ones simply don’t have the opportunity to speak up. And I feel that I have to do this for them. To speak for Bohdan, and at the same time, for other political prisoners. Because I have this opportunity and there are no risks for me that they have.

“We later learned that he had been tortured, but it was obvious even without the documents: a confused look, crumpled clothes, a frightened face”

You said that one May day you saw the building of the occupation administration of Yevpatoria doused in blue and yellow paint and immediately sent it to Bohdan. However, you never received a response. Do you remember your first reaction when you learned about Bohdan’s detention? How did you even find out about it?

It’s true. We were constantly texting back then – literally 24/7. I received the last message from him after midnight. And I couldn’t even imagine that this would be the last message before he went to do what he did.

Photo: “RIANewsCrimea”

Photo: “RIANewsCrimea”

In the morning, I woke up, opened the news and saw a photo: the door of the occupation administration in Yevpatoria was doused in blue and yellow paint. I immediately sent the news to him, jokingly asking: “Have you got partisans there?” and laughing. He didn’t respond. And I didn’t even suspect it was him.

And this, by the way, is a big problem in our information field. I don’t want to criticize the media, but then I realized how much depends on whether there is a name in the story. Because they often write: “In Kherson or Simferopol, a woman was detained who allegedly committed a crime. Without a name, without a face. And society perceives this as something distant, accidental. And behind every such news item is a living person, a political prisoner, a story.

Before this happened to us, I did not realize the scale of the problem of political prisoners. I only knew about Oleh Sentsov. He was released in 2019 and it seemed like the last big release. And then – silence. No exchanges, no guarantees, no protection. People simply disappeared into the system and were forgotten.

And only later did I realize that our conversations with Bohdan the week before his act were different. He was agitated, a little withdrawn, and answered briefly. I asked what happened, but he didn’t explain anything. And then I lived in a whirlwind of events – my parents were trying to leave the occupation, there were shelling, the Kyiv region, anxiety… Everything came crashing down at the same time. And I simply didn’t pay attention to his condition, although I really regret it now.

After that night, he disappeared. I wrote, called, left voicemails – no answer. The next day I started feeling anxious. And on the third day I started looking for his friends in Crimea, writing to everyone I remembered. Silence.

And one day, late at night, I simply entered his name on the Internet – Bohdan Ziza. And the first thing I saw: the news that he had been detained. Only one russian-language publication wrote about it. “Bohdan Ziza was detained for dousing the administration door with paint.”

I was in shock. I started to have hysterics. Everything fell apart at the same time. And then the video of his “confession” appeared – it was obvious that he was forced to read from a piece of paper. We later learned that he had been tortured before, but it was obvious even without the documents: a confused look, crumpled clothes, a frightened face.

This was probably one of the most emotional blows of my life. But the very next day we started acting. At first, it was chaotic, instinctive. We spread the news on social media because no one else was writing about it.

I had never worked with the media before, I didn’t know how to speak publicly, what to do. But I realized that I needed to raise awareness – I started writing to journalists, bloggers, and influencers. People started spreading information, and that was the first step. Then we created a support page so that his story wouldn’t disappear, so that people would know about him.

When the story started to gain publicity, I started getting invited for interviews, and that was the first time I felt that Bohdan’s act finally had a name. That there was a specific person behind this news. I really lacked that.

And it was also scary to realize how many people remain nameless. Most political prisoners, unfortunately, remain in the shadows. No one knows about them, no one fights for them. Their stories don’t make it into the media because not every one of them is “bright” or “convenient” for headlines.

Although in recent years, a great step forward has indeed been made – thanks to human rights activists and journalists. We see Nariman Dzhelial, Leniie Umerova, Vladyslav Yesypenko returning. This is a huge effort and at the same time a huge risk for everyone. Because even if a person serves the full term, it doesn’t mean that he/she will be released peacefully: in russia they can always come up with a new case, a new term, add another 5, 10, 15 years. And this is the reality in which people live.

I found out about it all when I “Googled” his name. And a few days later, news appeared on the FSB website that Bohdan was allegedly facing 15 years in prison. We were all in shock. His friends, acquaintances, everyone who stayed in touch at the time, couldn’t believe it. Fifteen years – for paint. But that’s when we first really understood who we were dealing with. russia doesn’t care. And even those who haven’t done anything get their 10-15 years simply because they can.

“Even the word “shelter” can be a reason for blocking a letter”

How do you receive letters from Bogdan?

We are currently corresponding through a third person who is in the territory temporarily under russian control. This is possible thanks to the “Zona Telecom” service, through which we send letters. Letters arrive quite quickly, however, there is censorship.

Most of our letters simply don’t get through. Often, in response, he writes that he hasn’t received anything, and is worried why I haven’t written. I understand what I’m writing, but the letters are simply blocked. This is one way of exerting moral pressure: censors simply block letters, seeing the context of the correspondence – for example, that it is important for us to stay in touch now because he is feeling unwell, or when I share my experiences.

There is also a mechanism for sending physical letters from abroad: they can be sent from any country, including through russia. Such letters can take months to arrive, but it’s one way to convey a message, photos, or something else.

However, these letters are also subject to very strict censorship, and not all of them reach the addressee. And one more nuance – correspondence is only possible in russian.

What are you writing to him about?

We try to keep a neutral tone in our letters, because everything goes through censorship. And even seemingly safe letters sometimes don’t get through.

Most often, we communicate about ordinary things – about health, well-being, about everyday life.

Bohdan is very worried. They have a TV in their cell that constantly broadcasts russian news, and they create a very disturbing, distorted information background there. When there is a shelling, especially in Kyiv, he is shown it from a completely different angle – as if everything was catastrophic, as if russia “almost won.” And this makes him anxious.

At such moments, he starts writing more often – asking what’s really happening, asking us to tell him a little about the real situation, about how we live, whether we go to a shelter, how we feel.

But, of course, we can’t write openly. These letters are not at all like the usual communication we used to have – in messengers or in person.

Now, every word should be chosen very carefully. Even common phrases – for example, that I went to Lviv, or that I am now in Kyiv – may not pass the censor. And even the word “shelter” can be a reason for blocking a letter.

So, we actually communicate with hints, little codes. It’s like you’re constantly solving a puzzle, trying to convey something important between the lines so that the letter gets through. It’s very difficult morally, but otherwise – no way.

How do you feel when you hold a letter from Bohdan? What do you expect to read there?

This, perhaps, can be called a kind of therapy. Because Bohdan is the kind of a person in my life who always appears exactly when I need him the most. It has always been that way.

We are adults, we each have our own lives. Before the start of the full-scale war, we communicated constantly, but still with pauses – as happens between close people. And when it was becoming hard for me, when I was sad, Bohdan would appear. It’s always been like that with us. It’s a connection that doesn’t disappear even when you’re silent.

Now this story continues through letters. There are moments when I miss our conversations terribly – and that’s when, as if by a strange coincidence, his letter arrives. And he always has words of support in them, as if he feels that I need that particular phrase right now. It’s a very special feeling.

When I receive a letter through “Zona Telecom”, I always put it off until the evening to read in silence. It’s a small holiday for me. The letters are different – sometimes two or three pages, sometimes ten. And each of them is like a breath of living presence.

And recently something very special happened. Bohdan managed to pass me a real, physical letter – handwritten. He signed a card, even drew something small, and sent it through friends from Georgia. When I received this envelope, I felt something incredible. I was holding in my hands the sheet that he held a few weeks ago – it was a feeling of real touch. We haven’t had this opportunity for many years. It was very moving.

I also decided to respond – I wrote it by hand and sent it abroad. And when he received the letter, he wrote to me: “Oh my God!” – it was that emotional for him. In those conditions, where there is no sun, no space, no familiar things –receiving such a letter means touching life.

I also joined the “Letters to Free Crimea” initiative. I don’t know how many of them arrived, but it was fundamentally important for me to send these postcards, written by people by hand. They are written by those who have never seen Bohdan, but sincerely admire him.

After his act, all his former friends from Crimea turned away from him. Some decided to accept the occupation, some went to russia and disappeared. But instead, completely strangers from Ukraine appeared and wrote him incredibly warm words. They say that his act is inspiring, that they want to know more about him, and ask him questions.

It is very important to me that these letters reach him. I am saving the ones that are written in Ukrainian and would not pass through censorship to give to Bohdan when he returns. And I send abroad the letters that have a chance to make it, so that he can receive at least a fraction of that warmth, that living connection, which he lacks so much there.

“This is probably another part of this story – when war divides not only countries, but also families”

Immediately after your brother’s detention, you began actively making posts on social media dedicated to Bohdan. What was the turning point for you when you decided you had to speak publicly about it?

You know, there are situations in life when you just act. You don’t have a clear sequence of steps, you don’t understand what will happen next – you just do what you can. I had one goal: to make as many people as possible know about Bohdan. Because among a large number, there is always someone who can help.

I must have been running on pure adrenaline at the time. It seemed like all I had to do was tell, and someone important would hear, intervene, and we could free him. I didn’t even think that he could actually be given 15 years. Moreover, that he would serve the entire term. Now I understand that there are different scenarios, and although we all hope for an exchange, we must be prepared for anything.

Later, we were invited to join the special project “Train to Victory.” There was a series of carriages dedicated to the resistance in the occupied territories, and Crimea was represented by Bohdan. His story, his actions became part of this great canvas.

The occupiers understood that there was no one else to look for him except us. And that’s why I felt: if we didn’t make a fuss, they would simply “lose” him. They could torture him, hide him, and no one would even know. I was afraid that they would decide that no one was waiting for him, no one was fighting, and they could do whatever they wanted.

That was the logic. At the time, it seemed to me that it was 50/50: either we would help, or we would make things worse. But the option of “doing nothing” simply did not exist.

As for grandma… You know, we don’t keep in touch with her. She has completely different political views. From what I know, she most likely believes that Bohdan was “recruited by Ukrainians.” She says: “It was your Ukrainians who incited him.” It’s hard for me to understand this, but, unfortunately, there are many such people, and not only in Crimea. She certainly worries about him like a grandmother, but some things between us remain unacceptable. And this is probably another part of this story – when war divides not only countries, but also families.

“I really lacked a clear “road map”: what to do, where to write, how to find a lawyer”

What support do you think the families of Ukrainian political prisoners need today?

Families of political prisoners need very different types of support – both moral and practical. In my case, informational support was the most important. When all this happened, I simply didn’t know where to run, where to start, who to turn to. I really lacked a clear “road map”: what to do, where to write, how to find a lawyer. A person in such a situation is in a state of shock, and any specific instructions or advice is a support.

But speaking more broadly – about all families of political prisoners, especially Crimean Tatars, who often have children left without parents – financial assistance is also critically important. Everything is expensive: lawyers, shipping, travel, even the ability to deliver a parcel or letter. One lawyer’s visit can cost several thousand hryvnias, and that’s despite the fact that I still need to find someone who can get there.

I was lucky that there were people nearby who helped me: Olha Skrypnyk, human rights organizations, who literally took everything upon themselves at the beginning. But, unfortunately, such support is not systematic. Often, families have to independently search for someone who can help, communicate with dozens of organizations, and spend weeks until a specific solution is found.

Therefore, in my opinion, what is most needed today is systemic legal, financial, and informational support. More communication: so that people know where to turn, which structures really help. Because until a person finds himself/herself in such a situation, he/she doesn’t even realize that there are the same presidential representatives who can intervene, advise, and support.

“This is his little world, his proof that somewhere out there is freedom, and it will definitely be waiting for him”

What do you think keeps him morally alive there, in those conditions?

I don’t even know what else could be holding him together in addition to the letters. Everything hinges on this connection – on the letters, on the feeling that he is not alone. It is the only thread with the outside world, his only contact with life beyond those walls.

Photo taken from Bohdan Ziza’s Instagram.

Photo taken from Bohdan Ziza’s Instagram.

It’s hard for him now – he’s a little sick, often doesn’t have the strength to respond. He says he has a lot of thoughts, but it’s hard to describe them. That’s why he sometimes just writes open letters – to everyone at once. And I see that people’s support, these hundreds of words that reach him – is what really keeps him going.

I always remind him that he doesn’t have to be strong every second, that he doesn’t have to answer to everyone or pretend that “everything is fine.” Because it sounds strange to hear “everything is fine” from a man who has been in a russian prison for more than three years. But it’s his way of holding on, his internal defence.

I think he is sustained by the feeling that he is remembered, that life goes on and waits for him. I constantly send him photos – moments of our lives, ordinary everyday things. He then says that he hangs them by his bed, puts some under his pillow, some – next to himself. This is his little world, his proof that somewhere out there is freedom, and it will definitely wait for him.

“Nobody cares about the health of prisoners”

You said that Bohdan has health problems. How is his access to medical care? Is it provided at all?

Medical care in captivity is very poor.

Bohdan has skin problems – either because of the conditions of his detention or an allergic reaction, we still don’t know for sure. Some of the medicines that volunteers deliver are simply not allowed through. Just the other day, two of our parcels with medicines were returned without explanation.

There are even more serious problems – he needs to take antibiotics, which the local medical unit simply does not have. And the medical unit there is more of a formality. No one cares about the health of the prisoners. He was lucky that once there was a medical worker who really paid attention to him and helped him, but she went on vacation – and everything stopped again.

The most painful issue now is teeth. For most political prisoners, this is where the problems begin: a complete lack of sun, vitamin D, no walks – they haven’t gone outside for over six months. The body weakens, and this immediately affects health.

But the worst thing is the so-called “dental care.” In fact, it is torture. Teeth can be extracted without anaesthesia, sometimes even healthy ones, and without any subsequent pain relief. Some of the prisoners who are put on duty in the medical unit then simply bully others – “working out” their position. That’s why Bohdan is afraid to go there.

We are currently trying to find any way to get him medication or get him examined by a doctor. But, as far as I know, this is practically impossible. There is a very illustrative example of Iryna Danylovych – she has been suffering from complications after otitis for a long time, she can hardly hear, and still does not receive medical care.

And there are hundreds of such stories. Some have heart problems, some have high blood pressure, and some simply die from simple things that are easily treated under normal circumstances.

For a long time, we held onto the idea that Bohdan was young, strong, and always had good health – and that saved us. But, unfortunately, even that doesn’t last forever. So, the main task now is to try to somehow help him cope with these problems.

We, of course, have hope for exchanges, but real statistics do not give us optimism. Therefore, we cannot just wait – we must act: send meds again and again, look for any opportunities, hope that he gets at least one parcel. The main thing is not to be too late.

“One can pay for any word with freedom”

Do you feel that Bohdan influenced others? That his act was more than just a protest?

One hundred percent yes.

At the very beginning, many people from Crimea wrote to me: they shared that they also stayed there, that they shared his position and admired him very much. Bohdan became an example of courage for many.

There really are resistance movements in Crimea – they just operate very quietly, imperceptibly, because any word can cost one’s freedom. But I am sure that his story inspired many – some to action, some simply to believe that all is not lost, that even in such conditions it is possible to resist.

At the same time, russia used Bohdan’s story in a classic way for itself – as a tool of intimidation. He was shown on national television, forced to “apologize” on camera. It was clear that he was scared. He was immediately called a “recidivist”, a “terrorist”, creating a propaganda image: saying, this is what will happen to anyone who tries to protest.

If we hadn’t raised the fuss then, this story would have simply disappeared – it would have been forgotten in russia and even in Ukraine. Because, unfortunately, for the occupied territories this is almost a familiar, “ordinary” story. But I see that it really touched people in Crimea – and this is probably the most important thing.