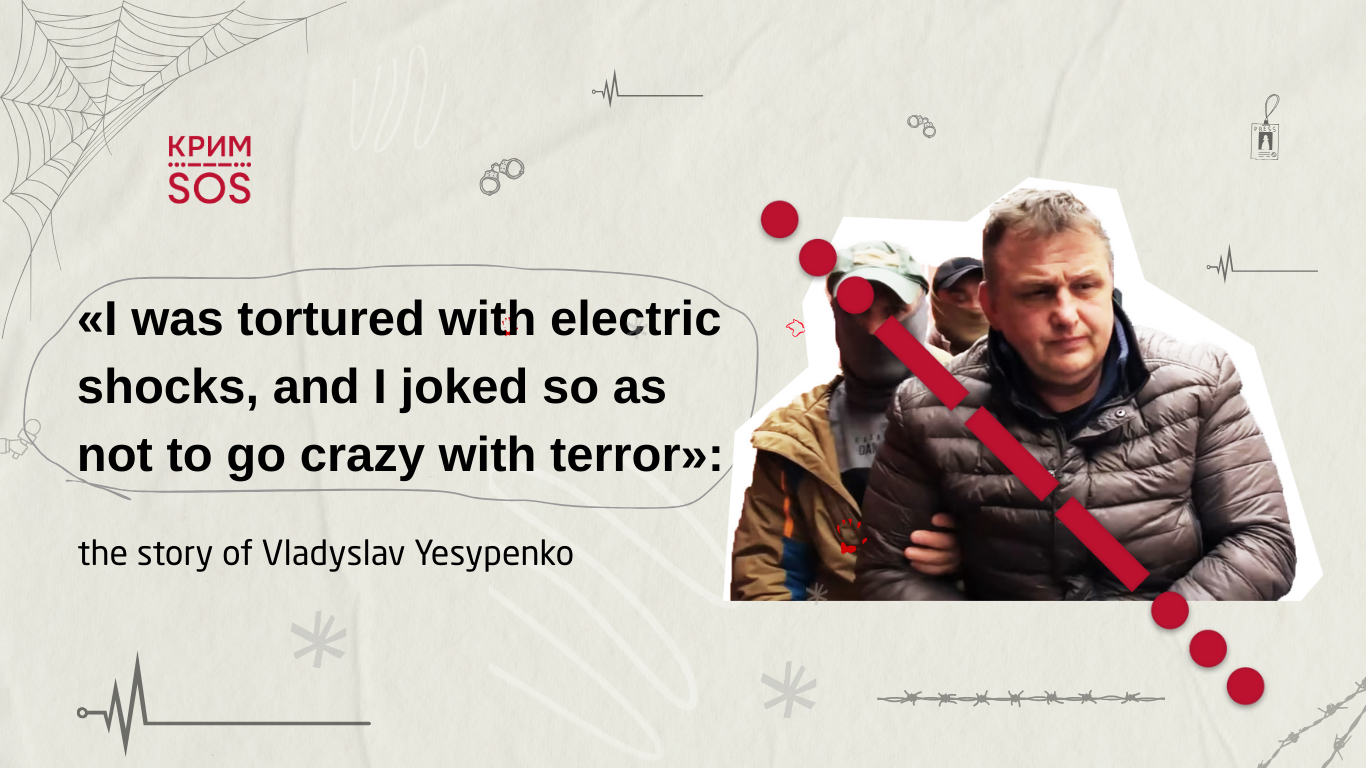

“I was tortured with electric shocks, and I joked so as not to go crazy with terror”: the story of Vladyslav Yesypenko

26 / 08 / 2025

It snowed in Crimea. For several minutes he stood barefoot on the cold, grey ground outside the prison walls – just to feel alive. He was tortured with electric shocks and beaten. During breaks, they allowed him to wash his bloody face. Meanwhile, they drank coffee and talked about everyday life. Then they tortured him again, and he joked so as not to go crazy with terror. For this, he was beaten even more brutally.

For years in captivity, he trained his emotional resilience, and when he saw his family for the first time in many years, he couldn’t show how happy he was. And now – he is getting used to freedom. Because even freedom, after torture, is perceived as a trap.

Through the eyes of Crimean political prisoner Vladyslav Yesypenko, we show what his life was like over the last 4 years. How an ordinary dream of moving to Crimea turned into a mission – to show the world a real picture of life under occupation, and what the prisoners of the Kremlin have to go through.

Your wife once said that you were both originally from Kryvyi Rih, and you only moved to Crimea in 2013 because it was your shared dream. Why was Crimea such a dream for you back then? How did you live there before the occupation?

Vladyslav and Kateryna Yesypenko. Photo from the couple’s family archive.

Vladyslav and Kateryna Yesypenko. Photo from the couple’s family archive.

Yes, it was a mutual decision by Kateryna and me. We wanted to live in a cleaner, ecologically safe place, because Kryvyi Rih is a very polluted city. We also dreamed of living by the sea.

We moved to Sevastopol a little over a year before the occupation. There was almost no time for rest, because we were actively developing our business – I was involved in real estate. In our free time, we attended theatre. We loved the Sevastopol Drama Theatre very much. Kateryna was a fan of actor Oleksandr Poryvai – we often went to plays where he played the main roles.

Later, we had a daughter, Stefania, and, like every young family with a child, we were busy. But when we had free time, we were going to the sea, walking in the Victory Park. We often went to the suburbs of Sevastopol, where there were few people. These were our “quiet places” where we could be alone, just the three of us – without the hustle and bustle, closer to nature.

“In a matter of days, it became clear: the peninsula was completely blocked”

Where did the occupation of the peninsula find you?

We were in Sevastopol and saw everything with our own eyes. We saw how the headquarters of the Ukrainian Naval Forces was seized, how military vehicles were moving. And at the same time, we heard this cynical lie from Putin that “they were not there.” It was very painful to watch.

The main protests took place in Simferopol, and in Sevastopol, checkpoints quickly appeared and roads began to be blocked. I remember how some drunk “Cossacks” appeared on the roads (they were members of an illegal armed formation – ed.). I understood that something had to be done. I tried to reach out to representatives of the UDAR party – I even got their contacts. But the situation unfolded very rapidly, literally in a matter of days it became clear: the peninsula was completely blocked. There was no longer any room for resistance, because saying anything out loud became dangerous.

February 26, 2014. Activists protest outside the walls of the Verkhovna Rada of Crimea in Simferopol. Photo taken from Refat Chubarov’s Facebook page.

February 26, 2014. Activists protest outside the walls of the Verkhovna Rada of Crimea in Simferopol. Photo taken from Refat Chubarov’s Facebook page.

“It became clear: this was not a temporary occupation – they had come for the long haul, and the struggle would be long”

How did you come to the decision to leave the peninsula?

At first, there was still hope that everything would turn back. I remember when we interviewed Aksionov (the so-called head of the temporarily occupied Crimea – ed.), he said: if people do not support russia in the “referendum”, he would resign. But even then, it was clear that all this was a farce, and the real goal was completely different.

Somewhere deep inside, there was still a belief that we could return Crimea by military means. But it quickly disappeared. It became clear: this was not a temporary occupation – they had come for the long haul, and the struggle would be long.

I didn’t want my daughter to wear St. George ribbons, sing Soviet songs, or live in this distorted reality.

I remember once on May 9th I saw a family – all in camouflage, even a small child with “awards”. They were walking with balloons in the shape of tanks and shouting: “We can do it again!”, “russian spring!”. It looked like mass madness. And the scariest thing was that many people were really happy, sincerely waiting for russia.

Then Kateryna and I finally decided: we would not participate in this. We had to leave.

“I did not yet understand how harshly, radically the FSB was ready to act – and not only towards me, but towards all dissenters in general”

In the territory controlled by Ukraine, you began to cooperate with Krym.Realii as a freelancer and repeatedly went on business trips to Crimea. How much risk did you feel at that moment and what was your personal motivation?

I understood that something needed to be done, but I didn’t have a clear plan at first. I started filming what I saw: how the Ukrainian Navy headquarters was being seized, how russian soldiers without chevrons stood next to local elderly people to create a picture of “popular support.” I recorded the movement of russian military equipment.

At first, I thought I was just filming it for history. But one day, standing near the Ukrainian Navy headquarters, I saw foreign journalists interviewing the head of the Ukrainian Navy’s medical service. He said: “I have lived in Ukraine all my life and still support it, and now they call me an occupier. For what?” His genuine surprise and pain touched me. I went over, shook his hand, and said, “I support you.” Journalists saw this – as it turned out later, it was the Arab TV channel Al Jazeera.

They came up to me and asked, “Aren’t you afraid you’d be arrested for your open stance?” I replied that I was not afraid and that I would say what I thought. So, they offered me an interview and I agreed. We went to a quiet place so as not to be in danger: at that time, the FSB and members of the illegal armed formations were already patrolling the city, and any manifestation of the Ukrainian position could result in arrest.

The interview lasted almost an hour. I said that many Ukrainians in Crimea did not support the occupation, and I was one of them. Later, the story showed fragments of my speech, as well as Refat Chubarov’s commentary. It was very important for me. I was proud that my stance was voiced publicly, alongside the voice of the head of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People.

As for the risks, when I started traveling to Crimea as a freelance journalist for Krym.Realii, to be honest, I didn’t fully realize how dangerous it was. Yes, I saw that some colleagues were detained, some were banned from entering, some were deported. Our colleague Mykola Semen, for example, was sentenced by the occupation Zaliznychnyi District Court of Simferopol to two and a half years of suspended sentence with a probationary period of three years and a ban on engaging in public activities.

There were certain restrictions, pressure, but at the time it seemed to me that all this was a limit. I did not yet understand how harshly, radically the FSB was ready to act – and not only towards me, but towards all dissenters in general.

“It was important to me not only to film the material – I wanted to see the reaction of people who have been living under occupation for several years”

Do you have any materials that you filmed for Krym.Realii during your business trips to Crimea, but which never made it into the public space?

Of course, some materials have survived. For example, I have videos where people simply shared their opinions. Some of them were published by Krym.Realii, some were not. It’s normal, not everything gets into the public domain. But even those recordings that weren’t made public were of great importance to me.

Sometimes I acted, perhaps a little daringly. For example, in Armiansk or Krasnoperekopsk, I simply approached people and said: “Good afternoon, I am a reporter for the Ukrainian project Krym.Realii, I want to ask you a few questions.”

It was important to me not only to film the material – I wanted to see the reaction of people who have been living under occupation for several years. And you know, no one ran to the police, made accusations, or threatened. People responded.

Did such interviews pose a risk to your respondents?

To be honest, everything seemed different back then. There were no waves of mass arrests, no total fear.

Today, the situation is different – for example, acquaintances from Bakhchysarai told me: at a party, people turned on Verka Serdiuchka’s songs, and the police immediately came. They said: you do it one more time – there will be a report, and then a criminal case.

And in 2016, I remember, my friends and I were gathering. We could turn on the Ukrainian anthem, and no one was afraid that the occupation security forces would arrive.

It was easier then. And, probably, there were fewer denunciations. Systemic repressions, mass pressure – all this became more frequent after 2022. Until then, the persecutions had been rather selective.

Were you subjected to pressure or persecution for your journalistic work in Crimea long before your arrest?

I was quite careful. My face was never in the frame, and I didn’t openly voice a pro-Ukrainian stance either. I realized that I had a clear journalistic task – to record events, collect material, and not put myself in danger at the same time.

I didn’t go around with flags, I didn’t provoke. Sometimes I even “adjusted” to the situation. For example, if I was filming a pro-russian protest, I could say a few “right” phrases to gain trust, film the story from the inside, and show the true face of these events.

This allowed me to remain unnoticed and do my job – without unnecessary risks at that stage.

“During a break from the torture, they took me to the toilet, I was spitting blood because I think I bit my tongue. And at that time, they were drinking coffee, talking calmly among themselves. Absolute contrast”

What happened on the day of your arrest?

It was March 10th. I was driving towards Alushta, and I was stopped by FSB officers near the village of Perevalne. First, they searched the car, and then took us to the car, in which they allegedly “found” a grenade – it was lying right on the driver’s seat. And at that moment I realized that serious problems had begun, because a grenade had been planted.

Detention of Vladyslav Yesypenko in Crimea by FSB officers.

Detention of Vladyslav Yesypenko in Crimea by FSB officers.

Among the security officers there was one – a stout man with blue eyes, later I learned that his name was Denys. He immediately started pressuring me: sign the papers. I refused. Then he said: “We will go to a place where you will sign everything. Do you understand?”

At first, I thought – well, at most, they could inject some truth serum. But everything turned out to be much simpler and more cruel.

They drove me for about an hour. Then they took me to the basement, stripped me naked, and started torturing me with electric shocks. Without any words. It lasted 3–5 minutes. Then – beatings and electric shock again. After that, they put me on a chair and started the “interrogation”: who was the curator from the Security Service of Ukraine, how was I recruited, what information did I pass on…

I realized that this was all standard procedure, aimed at only one thing: breaking a person. Then I caught myself thinking that this is how people were tortured in concentration camps – first they were stripped naked, then they were broken physically and mentally.

What could you see on the faces of the executioners as they did this? What emotions did they have?

No faces were visible – everyone was wearing balaclavas, only their eyes. But even through the eyes it was clear: no emotions. Complete detachment. They acted as if they were performing a routine technical job. Like a turner who stands at the machine and calmly grinds a part. Nothing personal – just a mechanical action.

During a break from the torture, they took me to the toilet, I was spitting blood because I think I bit my tongue. And at that time, they were drinking coffee, talking calmly among themselves. Absolute contrast. Their attitude was towards it as a normal working process.

And then I thought: this man would go home in the evening. His wife would meet him, his child would hug him. “How was your day?” – “Well, there’s a lot of work, dear.” They would sit down to dinner. And not a single thought that a few hours ago he had tortured a person. This was part of their job, which they performed quite responsibly.

These were FSB officers. I divided them into two types.

The first were the so-called “heavyweights.” These were FSB special forces fighters, well-trained physically, constantly in training. As they themselves said, they trained for several hours every day, had parachute training, studied first aid, and ran long distances. These were the performers of power tasks – strong, hardy, but, frankly, quite limited intellectually. During our conversation, when the arguments were over, one of them simply fell silent, and then blurted out: “I’ll shoot you in the leg right now.” That was the level of the discussion.

The second type was the so-called “analysts.” Investigators, analytical department – thin, always in suits, white shirts, with hairstyles, ties. If you saw someone like that on the street, you would think that they were a middle manager in some bank or office. But they knew very well what to do and how to do it. It was these “office workers” who fabricated the cases, skilfully and methodically.

“I was threatened with death, and I also heard threats against my family”

Fabrication of a case, arrest, torture, pressure on the family. How did you survive the first year of imprisonment?

First, there was not only physical pressure, but also strong moral pressure. I was threatened with death, and I also heard threats against my family.

When I spoke about the torture in court and was allowed to speak to impartial lawyers for the first time, everything changed dramatically. After that, I was taken back to the same basement where it all began. Denys, whom I was talking about, came and said: “I was summoned from Moscow because of you. Because you are giving evidence that does not suit us.” And again – threats. I thought then that everything was over. They’d just hang me on those bars.

It sounds wild, but even at such a moment, my brain was turning on some kind of black humour – probably as a way to survive. I remember when they were torturing me, I told them: “Guys, after what you do to me, I don’t even need to go to the gym anymore.” They only got angrier and started hitting even harder. But these thoughts, these jokes – they weren’t intentional. They just came on their own, as if my brain was trying to protect me from the horror that was happening. It was my way of not breaking down.

The death threats started right away – when I was first brought to the basement. One of them said bluntly: “You won’t get out of here. You simply won’t live anymore.” My heart started to pound then, I told them: “I have a heart condition, I might not make it.” And in response – absolutely coldly: “We don’t care. We’ll bury you in the forest like a dog.”

I was already clearly aware that I was outside the legal field, and they could really do anything they wanted.

Later, when I was admitted to the lawyers, one of them told me a story. He said: there was a case of a Crimean Tatar – he probably had a low pain threshold. He was tortured for a long time and cruelly, but he endured everything and did not sign anything. As a result, he was simply thrown out at the bus stop. People picked him up, took him home. He was treated, took his family and left Crimea.

Such stories are rare, but they do happen. They manage to break most people.

And in my case, while I was in that basement, absolutely nothing was known about me. Only later did the first video appear. It was posted on Krym-24. The interview was supposedly conducted by the general producer of the channel, Kriuchkov. But I clearly understood: this was not an interview. This was all staged. He was just an extra who was put in front of the camera to read out lines written in advance by FSB officers. No questions, no journalism. Just carrying out orders.

How do you feel talking about it, recalling it?

The brain somehow protects itself. Especially when it comes to prison – it seems to build a wall, blocking out certain memories. I just don’t want to remember certain moments.

But I understand: we can’t keep quiet about it. While I’m here, many of our political prisoners are still in prison. And every story like this is a reminder of them. It’s a chance to draw attention.

In Ukraine, people know about it and talk about it. But in Europe, it’s not always the case. Our diplomats, human rights activists, and international organizations are really doing a lot to raise this topic, but it’s still not enough.

Therefore, we need to speak out. We need to show. Without embellishment. Show how the russians torture Ukrainians so that they have no illusions. Because time will pass – and the same methods can be used against them.

“This interview was the first and, unfortunately, the last. After Kostia’s death, it took on special significance”

Despite the mass closure of Ukrainian media in occupied Crimea and serious pressure on independent journalists, you still took risks, continued to work, and showed the world the truth. And even in captivity, behind bars, you did not stop this mission – in 2022 you managed to interview Kostiantyn Shyrinh, who, unfortunately, died the following year due to lack of medical care. How did this opportunity even arise? What made it possible – and what prompted you to make this decision?

He and I were in the same pre-trial detention centre at the time, and we talked a lot. One day in particular was memorable when we were taken for a so-called “walk” – a small courtyard on the roof of the pre-trial detention centre where we were allowed to spend an hour in the fresh air. Kostia and I were in different courtyards. We didn’t see each other, but we often called out to each other.

The full-scale invasion of the russian federation into the territory of Ukraine began. And that day we were simply silent on the walk. Kostia was very emotional, a true patriot, he always reacted sharply to the lies of russian propaganda. He often argued with those who supported the “russian world”, especially with the so-called “Z” prisoners.

I remember him speaking indignantly about someone like this: “My God, he went to a Ukrainian school, graduated from university here, served in the Ukrainian army… And now Ukraine is an enemy for him?” It all hurt him terribly, he couldn’t accept it. He always spoke sincerely – with both pain and humour.

Kostia was like an older brother to me. I had two people in prison whom I considered brother and sister. Him and Halyna Dovhopola who is still in prison and is 70 years old.

Kostia had a difficult biography. He was in prison during the Soviet era, where he experienced many difficult moments. He was a very bright, wise, sincere person. A person who didn’t break down, who supported others. And even in those conditions, he found the strength to joke, hold on, and encourage us.

Once I suggested to him: “Kostia, let’s record an interview.”

And he replied: “What can I tell you? My life is a continuous adventure.”

I told him then: “You have no idea how important you are. You are like a beacon. People look up to you. People trust you. You are a man of action. This needs to be recorded.”

He agreed. I made a list of questions for him. The so-called “kites” – letters that are passed from cell to cell in prison, sometimes arrive in a day, and sometimes in three. These “kites” are very difficult to convey in a pre-trial detention centre, but he still received my questions and answered them after a while. During walks, we discussed certain issues with Kostia. This interview was the first and, unfortunately, the last. After Kostia’s death, it took on special significance.

Kostiantyn Shyrinh.

Kostiantyn Shyrinh.

How did this interview end up behind prison walls?

In such conditions, of course, everything is controlled and censored – officially there were no opportunities to pass interviews. But sometimes lawyers were coming to us, and it was through them that we could deliver letters. In particular, I delivered a letter to Kostiantyn’s daughter who lives in Kyiv. Then Kateryna contacted his wife, and she sent photos of their two children. Can you imagine how happy he was?

He spent a long time in Lefortovo, then he was transferred to another prison, and in total, he spent more than two years behind bars. And here – for the first time during all this time – a photo of his children. He kept those pictures in his Bible, they were black and white prints, but they had a huge meaning for him. And I was happy that I could at least help him with that.

Unfortunately, I was unable to conduct an interview with former political prisoner Nariman Dzhelial. We were on different floors of the pre-trial detention centre, I was literally shouting, asking if he would mind giving an interview – he agreed. But then he was often transferred, I was often taken to trials, and everything didn’t work out.

Another important person I spoke with in the pre-trial detention centre was Archbishop Klyment. He visited me, we talked for a long time, he read prayers in Ukrainian, and gave me printed texts. I reread them in my cell – it gave me inner strength.

I even started preparing an interview with him, but I didn’t have enough time – I was transferred further, to the colony. I believe I will finish writing this interview one day.

I also remember an interview with a collaborator – Kostiantyn Hermanov, a former deputy from Kerch, who switched to russia in 2014. But that’s a completely different story…

“Sometimes the connection was intentionally interrupted without explanation during a conversation with relatives”

Kateryna said that she very rarely managed to keep in touch with you, since she was in the territory controlled by Ukraine. Were you supervised while talking to your family? Were you forbidden to talk about anything?

Yes, communication with my wife was very limited. Almost no one had regular phones, because we were in the so-called “red zone,” and it was simply impossible to call a Ukrainian number directly. So, communication took place exclusively through the “Zonatelecom” system – this is a controlled communication channel for prisoners.

Sometimes the connection was intentionally interrupted without explanation during a conversation with relatives. Then I had to write a statement, go to the security officers, and ask what the matter was. They replied: “You said something wrong,” “You asked questions we don’t like.” They didn’t explain what they didn’t like. This happened often.

There were times when I couldn’t call my family at all for a month, a month and a half, or even two. I asked others who had the opportunity to at least somehow let my family know that I was alive, that everything was relatively normal.

Censorship was strict. Surveillance was constant. There were “snitches” in the pre-trial detention centre – people were put in cells specifically so that they would listen to what we were talking about, what we were writing, or if we were passing on any notes.

It was the same in the general regime colony. Among the prisoners there were those whom the administration promised benefits or probation if they would inform – not only on me, but also on others. For example, in my unit in Kerch (which consisted of about 60 people), there could be 5–7 such informants. They reported on literally everything.

One of them was our household manager, that is, a prisoner who was given certain powers to manage the household affairs of the unit. So, he went and reported to the administration that I was teaching my friend, the Uzbek Tursunov, the Ukrainian language. We were summoned for questioning: why? why? And the person simply wanted to learn Ukrainian, and I helped.

For them, this was something completely unacceptable. Once, even another prisoner said his name or patronymic in Ukrainian – not “Aleksandrovich”, but “Oleksandrovych”. He was immediately threatened: “Don’t you understand what war is? Why are you speaking Ukrainian here when our guys are dying at the front?”

So, any manifestation of Ukrainian identity or human dignity was a reason for persecution.

“I walked or ran 10 kilometres every night in an 11-square-meter cell”

Tell us about your day in captivity.

When a person is brought to the colony, it all starts with humiliation. The person is met with dogs, batons – they may even beat “as a preventive measure” so that the prisoners feel the “authority” of the administration. Then the person is sent to quarantine, and after that he/she is distributed to the so-called “units” to “correct himself/herself.”

There was an opportunity to work in the colony: in industrial workshops. They made various things there: benches, bus stops, even shields for trenches. This work was well paid, and some prisoners went to work – they worked with shields with hammers, did whatever they were told.

For me, this was unacceptable. Working for the occupiers was complicity. It didn’t matter what the help was – it mattered that it was help. I deliberately refused: no benches, no bus stops, no prison bars, I wouldn’t do anything for them. And although they couldn’t force us directly, those who refused were simply left in the barracks, within the confines of the unit.

Someone was cleaning the bathhouse, someone took care of the flower beds, someone was just sitting indoors. I tried not to participate in anything related to the system at all. Even when they invited me to play in the orchestra on May 9th – because I graduated from music school – I refused. To me, it looked like the concentration camps where musicians played while people were being led to the gas chambers. It humiliated me.

Vladyslav Yesypenko. Photo: Crimean Solidarity.

Vladyslav Yesypenko. Photo: Crimean Solidarity.

The most important thing for me was to do something, otherwise the emptiness would eat me up. I knew that if I didn’t control myself, I would go crazy.

There were prisoners lying on their bunks, smoking, playing backgammon, aimlessly killing time. But I didn’t want to just exist, I wanted to survive and remain human. We had a small community of like-minded people. We understood: if we break down, we wouldn’t get out. And if we get out, we wouldn’t be able to live on. That’s why we consciously built three main areas of self-preservation.

First is physical health.

I walked or ran 10 kilometres every night in an 11-square-meter cell. I invented exercises with flasks tied with ropes instead of dumbbells. In the colony, I ran up and down the stairs. People who didn’t take care of themselves lost both their health and will.

I knew I had to come out strong. Because after all this, I would still have to fight. And not just for myself.

Second is the brain.

I discovered chess for myself. I played 10–15 games a day. I looked for worthy opponents, developed a strategy. I never thought chess was so much fun. It’s an incredible thing – it focuses, makes a person think, keeps mind active. I regret not playing chess earlier. I also read. Although my eyesight was bad and there were not many books.

Third – new knowledge.

We were learning English. One of our friends knew the language well and taught us classes. I haven’t become fluent, but I already understand a lot of what I hear. And most importantly, I began to be interested in things that I did not have time for when I was free.

We also had a friend who was a doctor. He taught us how to provide first aid: how to do CPR, tracheostomy, what to do in case of a heart attack.

“The closer the release date got, the more anxiety grew”

What did you feel when you left the walls of the colony and what were your emotions when you saw your family for the first time in so many years?

The closer the release date got, the more anxious I became. It would seem that I should have been happy, but I knew who I was dealing with. FSB officers openly told me: “Your next term is 15 years.” I had no illusions. I expected that I might be intercepted right at the gate and taken away for a new case.

When my friends started congratulating me on my upcoming release, I couldn’t be happy. Inside, there was a constant expectation of a trap. I was thinking through all the options. Prisoners have few ways to protest: either hunger strike or self-harm. These are, of course, extreme measures, but in such conditions, it is sometimes the only way to make yourself known and not let yourself be destroyed in silence.

I was ready for such resistance if I was detained again. But the unexpected happened: I was met by my lawyer. We immediately left for Sochi, then moved on – towards freedom. Even when I was already sitting in the plane, I wasn’t completely sure. Only when it took off did I breathe a sigh of relief: alive, free, and out.

The route was long – through Armenia. And even there, there was still danger. russian intelligence services had great influence – even on border control. Ukrainian consular officers escorted me across the border separately. I remember the officers taking my passport and disappearing into another room. Then I prepared myself for the worst again. But they returned with the documents – and I realized: another barrier had been crossed.

In Armenia, I was met by a colleague from Radio Svoboda. Then – the Czech Republic, where my family was already there. And it was then, for the first time in many years, that I saw my loved ones again.

I thought that when I met my family, I would fall to my knees, cry, and kiss the ground. But no. Restraint has become a habit. It’s not customary to show emotions in the camp, and over time it changes a person. So, on the outside I looked maybe a little indifferent. But on the inside… on the inside I was very happy. I’ve just learned not to show it in public.

Vladyslav Yesypenko meets his family at Prague airport.

Vladyslav Yesypenko meets his family at Prague airport.

I couldn’t relax for a long time. Constant self-control is something you train for years in a colony. Willpower doesn’t come immediately. First, you just stop waiting for a stab in the back.

Perhaps because of this self-discipline, even in the colony I was treated with special respect. Some prisoners called me “sensei.” I trained, hardened myself, doused myself with cold water, even walked barefoot in the snow. Others started joining in – we were dousing ourselves with cold water together, doing exercises. I implemented rules: for example, for each bad word – 20 push-ups. And at first they joked, but they got used to it. People changed. Even those who were considered “hopeless.”

But there were times when I couldn’t stay calm. One of the prisoners began to publicly say that it was necessary to bomb not only the military, but also Ukrainian children. I warned him: if he says that again, I will either maim him or kill him. Yes, it could have been a provocation. But some things are beyond the limits of what is permissible. I remained a human being, but ready to defend dignity – my own and that of others.

Why were you walking barefoot in the snow?

This was my spiritual training. Snow is rare in Crimea. But when it did fall, it was a gift. I would go out barefoot, stand for 5–10 minutes. We would even throw snowballs with the prisoners, for which the inspectors would scold me and threaten me with solitary confinement. But I knew that this gave me strength. Energy. Feeling of control over myself.

Now I’m free and every day is a chance to do something meaningful. Even if I can’t express happiness out loud yet.