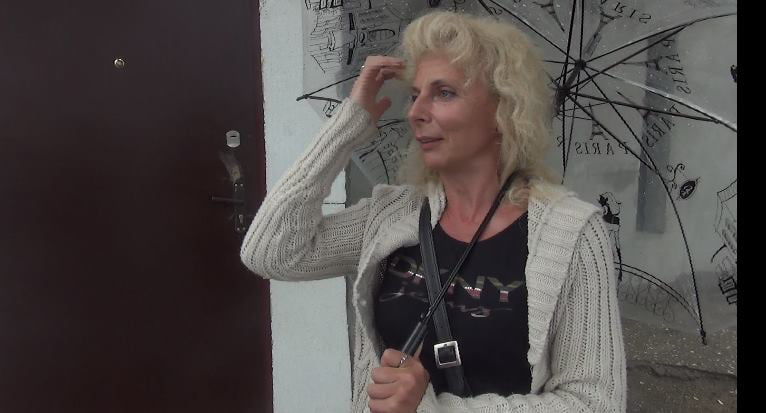

Halyna Dzhykaieva: “We forget what theatre was created for”

27 / 03 / 2025

Theatre studio “Na Moskoltse”, Art Centre “Karman”… Until 2014, these projects were iconic for the Crimean public and developed the underground scene on the Peninsula.

Today, the ideological inspirer of both centres, director Halyna Dzhykaieva, is forced to stay outside Crimea. However, the theme of the Peninsula does not disappear from her artistic agenda: both in Kyiv and Odesa, Halyna continues staging performances about Crimea and the Crimean resistance.

On the occasion of World Theatre Day, Halyna Dzhykaieva gave an interview to CrimeaSOS about how independent theatre developed in Crimea until 2014, why theatre activists were persecuted after the occupation, whether there is a difference between plays before and after leaving the Peninsula, and why “faith with clenched fists” is much more productive than dreams.

“I realize I am a completely whole person when I meet the dawn on Ayu-Dag”

Halyna, thank you very much for taking the time to talk. We want to talk to you about the theatre stage in Crimea — the stage that we remember and want to restore in the future.

First, I would like to ask how your journey in theatre directing began. And why did you decide to develop theatre in Crimea and stay in Crimea? At that time, as far as I remember, most creative people left the Peninsula and built their careers elsewhere.

The theatre I left and where I still am is an independent theatre. I worked in the state theatre for only a year and a half — in our Ukrainian musical theatre (the Crimean Academic Ukrainian Musical Theatre in Akmesjit, — ed.) and I never returned to the state theatre again. I had no desire to connect with the system as such.

It is very important for me to be free in my artistic expressions. I don’t want to be limited in anything or dictated what to do, or have any boundaries set.

At one time, I studied in Kyiv (Halyna Dzhykaieva graduated from the theatre faculty of the Kyiv University of Culture and Arts, — ed.) and in Kharkiv at the Department of Theatre Studies. These were correspondence departments. In theatre, practice is more important: you acquire knowledge and then apply it in practice.

I was very lucky with a master who didn’t hinder me, but guided me, saying: “Halechka, this is brilliant, but it’s no good. Look for something else”. And this approach inspired me a lot. It stimulated creativity.

Why didn’t I stay in Kyiv or Kharkiv? I would say that I’m a “freak” in an artistic family because I have no ambition. I am not interested in this pursuit of a name. Especially since back then in Crimea it was more important for me to climb a mountain and look at the sky. I realize I am a completely whole person when I meet the dawn on the cliff on Ayu-Dag — it is an incredibly resourceful state. For me, this is my creative state. I might be some kind of Buddhist (laughs, — ed.).

I enjoyed the thrill that theatre gave me. I earned money as a journalist, working at “Chornomorka” (Chornomorska Television and Radio Company, — ed.). And I did what was important to me, what “carried” me through creativity.

Everything was coming together by itself. Surely, when you’re going in the right direction, all the roads intersect for you, and you meet the right people along the way.

“Our viewers were probably the most active opponents of the occupation of Crimea”

Initially, there was the studio theatre “Na Moskoltse” (an independent theatre in Akmesjit, where Halyna worked from 1993 to 2005, — ed.), where the main artist, manager, and main director was Kosov (Volodymyr Kosov, — ed.). Then he left for the Ukrainian Musical Theatre. And after 2014 he became the chief director of the theatre, which is no longer Ukrainian — I don’t know what it’s called now.

And somehow, he got spoilt, went into a “kneeling state”. That was a blow to the breath. After all, when the theatre “Na Moskoltse” existed and Kosov was starting, it was something extraordinary for Crimea — such an experimental theatre.

Then we had “Karman” (an art centre in Akmesjit, which Halyna Dzhykaieva headed in 2011-14, — ed.). Everything creative and interesting that was in Simferopol could be “crammed” there. As I used to say, it was Hermione Granger’s handbag – small, but there was simply abysses in it! Incredible performances, art and gallery exhibitions, vernissages, apartment concerts, music — whatever you want.

Artists at the “Karman” Art Centre. Photo provided by Halyna Dzhykaieva

Artists at the “Karman” Art Centre. Photo provided by Halyna Dzhykaieva

We developed a non-governmental, underground theatre. Now, looking back, it was a conventional theatre. But we were looking for some new forms of theatrical language, new approaches to theatre. It was fun, wonderful, kind of a family story.

People who cared about us gathered there. Student activists, including Sasha Dvoretska (human rights activist Oleksandra Dvoretska, — ed.). This activist fraternity was closely monitored by the Security Service of Ukraine, and then the FSB. Those who were the SSU agents then all together became FSB agents.

Interestingly, I was already thinking about the correlation between views and tastes in art. For example, activists gathered in your theatre, those who were later persecuted by the FSB, and it was from their side that the main demand for this independent product came.

Yes, I can say that it was our viewers who were probably the most active opponents of the occupation of Crimea. Hena Afanasiev (political prisoner, activist, Ukrainian military man from Crimea Hennadii Afanasiev, who died in the war in 2022, — ed.) was a regular viewer of our performances, he was bringing his friends and acquaintances to our theatre.

As far as I know, you left the Peninsula due to persecution by the FSB, an increased interest. Can you tell me a little more about this?

You can read my story in the book “There is Land Beyond Perekop” (a novel by Anastasiia Levkova, — ed.).

Halyna Dzhykaieva in 2014. Photo from personal archives

Halyna Dzhykaieva in 2014. Photo from personal archives

When the occupation began, we were gathering in the theatre. Hena (Hennadii Afanasiev, — ed.), Toshka (director Antonina Romanova, — ed.), me. We formed first aid kits, parcels arrived at our address from Maidan to help the blocked soldiers, everything necessary — from clothes to helmets. Oleh (director, political prisoner Oleh Sentsov — ed.) drove them, Toshka also drove them. We stored leaflets before the “referendum”, Ukrainian symbols, etc. When we went to the rallies, we had all the flags with us.

Of course, there was a car parked outside the theatre with the words “Berkut” written on it. It stood there 24/7. And we realized that we were behaving badly.

When the “referendum” took place, we went underground. We decided that we needed to wait and see what it was like, not to endanger this peaceful resistance, the rallies. It could be dangerous, and we were advised to leave. Toshechka Romanova left for Cherkasy and never returned.

And I came back and, it seems, in June the FSB came after me and took me to talk to them. And in August, it was clear that I had to leave. And I left.

“The main task of theatre is to form a conscious citizen”

Returning to the topic of theatre, what performances and projects were in greatest demand? What interested the audience the most?

Then, as now, the greatest demand everywhere was for bourgeois drama, comedies, and fun. For example, I now live in Odesa, and this is where the greatest demand for fun is, even in wartime. Unfortunately, the “Soviet era” made our audience think that theatre is either a propaganda tool or that it should entertain. But we forget why theatre was created in ancient Greece.

Why?

Its main task was to form a conscious citizen of free Athens. This is the abyss into which our Ukrainian theatre has fallen and from which abyss we now have to climb out, because this is exactly what we do not have and have not had for many years. Theatre was not a tool for forming a conscious citizen in Ukraine. It was either propaganda or entertainment. Unfortunately, there was no intelligent theatre in experimental art forms.

If we talk about our performances, they were usually sold out. Some part of the audience were coming to our plays several times.

All the performances were different. For example, our activists very well received the social farce “I’m fine!?”. This performance was quite complex in terms of construction and perception. So, we didn’t show it often, and there weren’t that many people.

Photo collage from the performance “I’m fine!?”

Photo collage from the performance “I’m fine!?”

But the plays about love, the very beautiful plays by Tosha Romanova, gathered full halls. As well as mine — the “Stone Angel”, a plastic drama about love.

The performance “Stone Angel”. Photo provided by Halyna Dzhykaieva

The performance “Stone Angel”. Photo provided by Halyna Dzhykaieva

In fact, between me, the director who staged these performances and coordinated the work of the art centre, and the now director who works only with war themes, there is a black hole rather than even an abyss.

“The topic of Crimea must be raised on all platforms — including creative ones”

Do you continue working with the topic of Crimea, are any of your current productions related to Crimea? As far as I understand, most of your performances now are about war and military operations.

I would not distinguish Crimea, I would not put it separately, because Crimean history is an integral part of the war that has been going on since 2014. Since 2015, I have been working on the Crimean topic. I staged the play “The Case of February 26”, which featured people who were outside the walls of the Verkhovna Rada of Crimea on February 26, 2014 — members of the Mejlis, activists, journalists, etc. Not only Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians, but also representatives of other ethnic groups who gathered then under the flags of Ukraine.

In our theatre in Kyiv (underground theatre PostPlay, — ed.) we performed the play “My Crimea”. In russian it sounded like “My Crimea. Report on a trip that never happened”. It was a post-documentary, ironic and tragic performance.

We revived the topic of Crimea and the Crimean Tatars – I staged many performances working with this topic.

Performance “Grass Breaks Through the Ground”. Photo provided by Halyna Dzhykaieva

Performance “Grass Breaks Through the Ground”. Photo provided by Halyna Dzhykaieva

And in Odesa, we recently had a documentary show with the stories of immigrants, which mentioned the story of an elderly Crimean Tatar family. A major event is currently being planned in Odesa, which will raise the topic of Crimea in general and Crimean Tatars in particular.

It’s interesting that the Crimean Tatar issue remains in your focus. As far as I know, you have always been actively involved in it.

In my focus, yes. Unfortunately, I can’t say the same about other artists.

Performance on the occasion of the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Deportation of the Crimean Tatar People at the Railway Station in Kyiv. Photo provided by Halyna Dzhykaieva

Performance on the occasion of the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Deportation of the Crimean Tatar People at the Railway Station in Kyiv. Photo provided by Halyna Dzhykaieva

Indeed, there is such a situation, currently this topic is covered very narrowly.

Yes, and not only among artists. The topic of the future of the Peninsula as a territory, as a state entity, is now under great question. It is unclear what the future of Crimea will be. We need to raise this topic, discuss it, and work with it on all platforms — including creative ones.

“Dreams are unconstructive. I like to work with reality”

Do you maintain any ties with former colleagues who remained on the Peninsula?

No, I don’t write to anyone, even if we were on good terms. I don’t want to put people in danger. Even before the full-scale invasion began, I stopped communicating until better times, because it already “smelled of kerosene”.

There will be time – we will communicate, but for now we can wait.

We can dream about what will happen one day, after the de-occupation…

I don’t like to dream. Dreams are unconstructive. I’m pragmatic – if/when it happens, you have to be ready, you have to do this, this, and this.

And if it doesn’t fall to my lot, then let’s hope that our students will do it.

Yes, at least you can make some plans and projections rather than dream. But it’s difficult now.

Make plans and do what is most needed now, looking at the reality that can change at any moment. I love working with reality in both plays and performance. Because the material gives reality, the existing space-time.

Why look back or look forward? … But if we talk about the art form in which I work – documentary theatre – I make performances that would allow us to talk to the audience afterwards about what we should do with all this. To understand in which direction we should move.

Thank you very much for the conversation. I hope everything changes for the better.

Me too. I’m not dreaming, I believe in it. Dreaming is frivolous, and faith has clenched fists. Armed with faith, with clenched fists, we should move in this direction.