Elina Khodakivska: “I never liked russia because I knew what deportation was like”

4 / 04 / 2025

From serenity to occupation. Elina Khodakivska, an actress at the Between Three Columns Theatre, is a Crimean Tatar. Her childhood was filled with mountain landscapes, the sea, endless lavender, adventures, and theatre. However, the Peninsula was occupied, and she had to rewrite her entire life in a new notebook.

How did the occupation of Crimea change the actress’s life? What did she have to go through and how did these events affect her fate? We talk about it in this interview.

“It seemed to me that nowhere could be as safe as in Crimea”

Elina, first of all, thank you for agreeing to the interview. I would like our conversation to be sincere and frank, so first I will ask: What does Crimea mean to you?

Home… A place of power, but power in memories, I would say. Because now I don’t really feel that way about it after all these 11 years of occupation.

Now I understand that it was a long time ago, and it’s all really at the level of childhood memories. I no longer give this place anything special inside of me, because I understand that my psyche is protecting itself in this way so as not to suffer and not to start living in that past. At the same time, I dream that at least my children see and feel this place of power, as it once was for me. However, now I’m realizing that it actually existed some time ago.

At that time, it seemed to me that there was Crimea, and everything beyond was scenery. So, it means my childhood, all my memories, my place of security. It seemed to me that nowhere could be as safe as in Crimea.

You seem to know everything there; you can handle any problems. Everything is yours there. Everything seems to have converged at that point. And Crimea is land, it’s steppe, it’s endless lavender, it’s grape fields, it’s the sea, the hot pebbles that you walk on, and your heels just bounce off it.

Crimea is looking at Ayu-Dag and thinking that there is such beauty everywhere. When you are there, when you are born there and live there for a long time, it seems to you that it is like this everywhere. And, on the one hand, it is less appreciated, and on the other hand, reality hits you hard on the head when you go somewhere and realize that…it’s not the same. And even when they told me that there was a sea in Odesa too, and for the first 5 years or so, the trigger for me was when they told me that there was a sea in Odesa.

Then, when I started visiting Odesa more often, I also found some great love in this city. But, of course, this is not the same shore. I’m not saying it’s worse or better, it’s just a completely different energy, beautiful in its own way. But Crimea is a collection of all the incredible things.

When people ask me, mountains, or sea, I always say Crimea. Because in my mind they shouldn’t be mutually exclusive. This is the point where it all converges. So why should it be separate?

“We could have stayed in Crimea and become victims of propaganda”

Tell us about your roots. What was your childhood on the Peninsula like? What are your most vivid memories?

My mother is a Crimean Tatar, my father is a pure Ukrainian, from Vinnytsia. He moved to Crimea when he was about three years old. And my mother, I think, when she was in fifth or sixth grade. And they started dating from the school years. Well, by dating I mean: my father was running after her for a very long time. Then they dated for a couple of years. No one believed in that marriage at that time. And there is a memory from my childhood when my mother often said: “I told him that I had come to my historical homeland and would not marry any Ukrainian, only a Crimean Tatar”. Dad smiled, nodded, and then the three of us appeared. My brother, me and my sister.

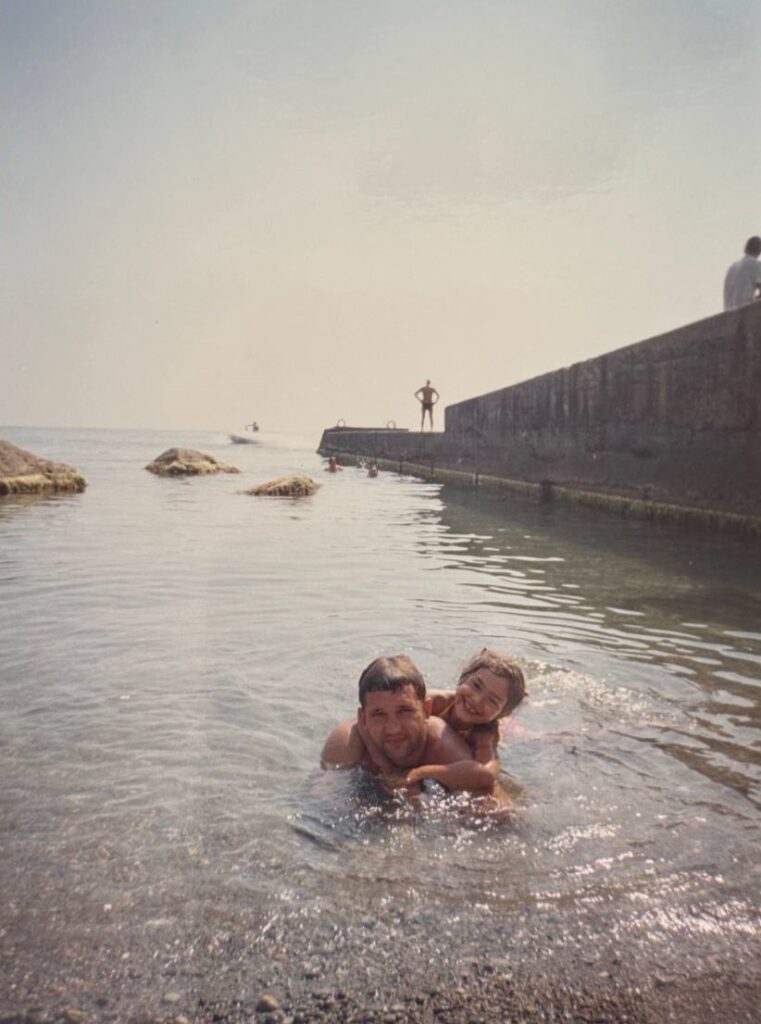

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Since childhood, I have felt this “duality” of blood within me. I always felt special when I told children in kindergarten or school that we celebrated both Easter and Eid al-Adha. Everyone was very sincerely jealous of me and said: “Do you have twice as many holidays at home?”. And I said yes.

Dad is Christian, mom is Muslim. We were not forced to believe anything; we were not baptized as children. Our parents decided that we would be able to choose our own religion when we are adults.

Recently, my brother and I were at our parents’ house and for some reason, my dad asked us whether we have decided anything. Then my brother and I looked at each other and answered something like “Why?”. We know that God exists, and you call Him that, mom calls Him this, but He is still one.

Then my mother asked what prayer I read before going to bed. And I replied that now it’s more often the Muslim one. But I remember very well in my childhood that on Epiphany, before going into the water, I recited the “Our Father” prayer, then the Crimean Tatar prayer, and then we went in the water. Because in my family, these things never contradicted each other.

My father can support my mother and fast during Ramadan. And there is no betrayal in this. If my father wants to observe an Orthodox fast, my mother supports him and gladly learns to cook lean dishes. This is a very bright moment, and now, remembering my childhood, I realize how lucky I was that nothing was against my desire. More holidays, more gifts, more guests, more travel.

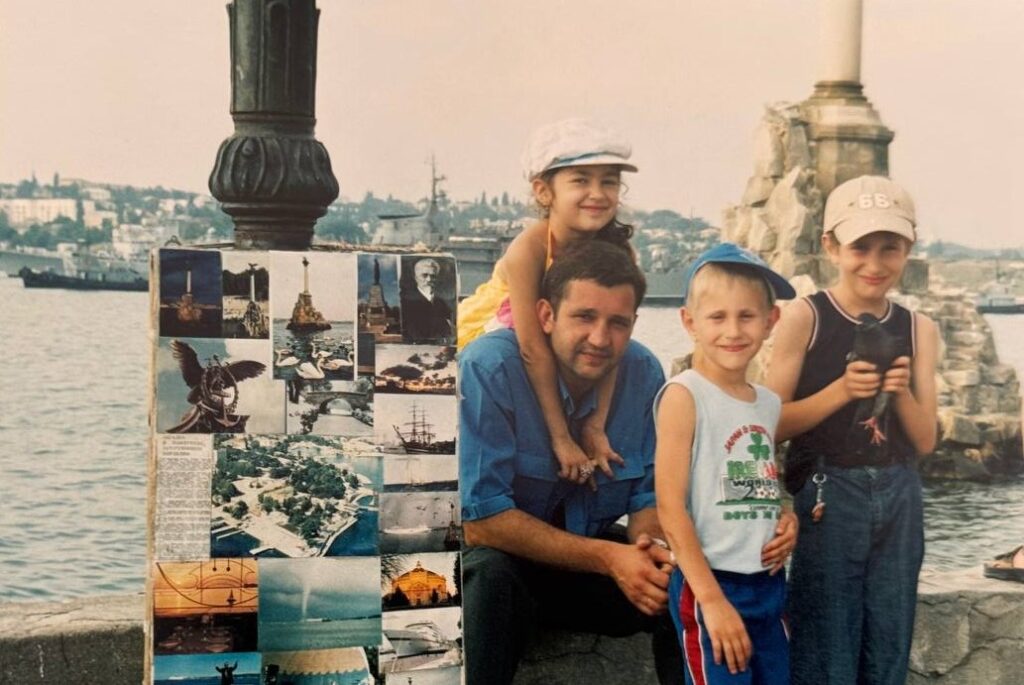

Another vivid memory from childhood – when my father came from work on Saturday and said: “I need 15 minutes of sleep and we’re leaving”. And no one knew where we were going. He really got up after 15 minutes and told me to get in the car. And we could leave on Saturday, go somewhere towards Yalta, spend the night, wake up in the morning, go towards Hurzuf, bypass everything along the coastline there. And then: “Oh, let’s drive to Kerch”.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

I regret that I didn’t realize then, “Oh, Crimea, oh, and here is this, and there is that”. It seemed so ordinary to me, I lived there, I already knew it all. And when I moved to Kyiv, when the “Crimean Tatar Tales” were created or the book “Crimean Legends” was republished, we opened it, started reading, and I thought, God, why have I never known this.

My mother talked about deportation, her homeland, and why they were deported. I knew Crimean Tatar songs. My aunt Maire Liuman constantly turned to folklore – songs, fairy tales. However, I didn’t realize it at the time and didn’t consider it valuable. It was only in Kyiv that I realized that I was a Crimean Tatar, a Ukrainian.

Another very vivid memory from my childhood is the theatre studio. Looking back, I understand that the Svitanok theatre studio in Simferopol, led by Alla Petrova and Oleksandr Polchenko, influenced my fate so much… Not only in terms of choosing a profession, but also in terms of one’s nationality, choice of country, and before that, choice of school.

Sometimes we sit with my parents, and my mother says: “I wonder what would have happened if I hadn’t taken you to that only Ukrainian-language theatre studio?”. And we somehow logically agree that maybe we would have stayed there and fallen victim to propaganda and believed all of this.

In the theatre studio, we grew up on Shevchenko and Lesia Ukrainka, we knew who Ostap Vyshnia and Ivan Franko were, they told us about Rylskyi, we read it, we did Ukrainian drama. In my bubble it was cool. And I understand that this small centre, a small oasis (the Svitanok theatre studio – ed.) in Crimea actually decided my fate. The entire Peninsula was saturated with the russian language and culture, they said, “Sevastopol is the city of russian glory”, but in that centre we felt so safe. It seemed to us that it was like this everywhere. And so, it turned out that we ended up in the only Ukrainian-language school, a Ukrainian gymnasium, where there was no russian, and somehow we moved in that direction.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Only then did I begin realizing that this was only our path, a Ukrainian-Crimean Tatar one, although I spoke exclusively Crimean Tatar until I was seven years old. Then kindergarten, school – and the language was forgotten.

The fact that I left Crimea in 2014 seemed like heroism to me. And in fact, I haven’t done anything since then to promote Ukrainian, let alone Crimean Tatar. Yes, I went to a Ukrainian school, and of course, I entered a creative Ukrainian university, but deep down I thought I was already cool enough because I didn’t succumb to this occupation. And there I was, such a hero, I crossed the border and all that. But in 2022, I realized that it was also my fault. It was my fault and my problem that I didn’t start talking about the qırımlı back then, that I didn’t switch to Ukrainian, that I didn’t start learning Crimean Tatar, which I only knew at a household level.

And because of this, we have a huge gap now between Crimea and Ukraine. A huge one.

And returning to the question of childhood memories – swimming in the sea for two days in a row, spending the night in some small rooms in Mykolaivka. It didn’t matter if there was a toilet and shower or not. We were by the sea! We came to “hang out”, “have a blast” with our parents.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

At night, my father could take me and my girlfriend, because we came with our families, and go bowling. At night. That was Mykolaivka. Everything was buzzing there all night. And he bought us two roses from an average old lady with flowers. A flower for each. And we were nine years old. And we were walking with those roses, father took us to a place, and there was a fountain. And we put our roses in the fountain. Why did we need a vase?

Crimea is an eternal summer in my head. It is an eternal carefree state. School, studio, English lessons, dancing. It’s like saying on a Wednesday evening: “Let’s go for a walk along the embankment in Yalta?” And everyone were like: “Let’s go!”. And that was totally okay. This was a trip, we planned it. We went there to eat ice cream on the embankment. This accessibility to all of this. Now I understand this accessibility. I didn’t appreciate it, I didn’t notice it, unfortunately.

People only appreciate it when they lose it. In general, you have very conscious parents, and this paternal spontaneity causes only positive emotions.

And my mom is quite spontaneous. She always supported all these ideas. We left Crimea – quite spontaneously. In the summer of 2014, when the Peninsula was already occupied, my brother and I were at the Sokil children’s camp. Suddenly our mother called him and said: “Tymurchyk, do you want to study in Kyiv?”. And he replied: “Well, I don’t know, I’ll think about it”. She said: “Well, think about it, you will study in Kyiv”. That’s it. The conversation was very short. After that, my brother left.

Later, during the first fall vacation, my mother and I came to visit my brother. I stayed in Kyiv for a week, and we decided to return to Crimea, pick up our documents, and I would move in with my brother. Well, the moment of separation from him was very difficult for me. And it was a condition that either they bring Tymur back, or I go there. Even though we were like cat and dog all our lives until Kyiv, right up until 2014. When there was no one to fight with, no one to talk to, no one to run away with, no one to paint graffiti on abandoned houses, I understood that a very big part of me had been taken away. And so, I moved in with my brother. And then, after the eighth grade, my brother and I raised the issue with our parents that we should take our younger sister out, too, because we understood that we didn’t want her to have a russian school certificate, that she should finish the ninth grade in Ukraine. And I went there, we packed her whole life into two suitcases. And that was it. So, there we were, the three of us.

So, your parents stayed on the Peninsula, and you and your brother and sister lived in Kyiv?

My parents moved a month before the full-scale invasion. It was just the way things were. We had been trying to persuade them for eight years, and they finally had the opportunity.

“We knew perfectly well that we would be next if we didn’t keep our mouths shut”

Were you affected by persecution by the occupation security services when you were still living on the Peninsula?

The persecution and searches did not specifically affect us. But my brother and I studied at a boarding school for gifted children in one of the villages of the Bakhchysarai area, so we felt this change very strongly there. Firstly, the flags changed very abruptly, we began to be taught the history of the russian empire, the russian language and literature very abruptly. And very often there were searches in this school.

Then there was a scandal because they found the Quran or perhaps some other religious literature. Then they tried to prove that it had been planted. There were searches. I remember well the moment when the “little green men” came in and asked all the students to sit in one building so that we wouldn’t see it.

They visited our neighbours several times. And the relatives of my mother’s friend, with whom we primarily left, suffered greatly. As far as I know, her brother is still in custody.

This did not directly affect our family. But we understood perfectly well, and our parents understood, that we would be next if we, the children, didn’t keep our mouths shut. Because our parents were aware of everything. And we wore coats of arms on chains, yellow and blue ribbons, until the last moment. And we were in the boarding school. Once there were a lot of people sent there, watching “Who? What? Where?”.

I remember when the Maidan started, my brother and I posted this huge photo of the Maidan on Vkontakte social media. And at that time, there was also Yarmak’s russian-language song “My Country Will Never Fall on Its Knees” in support of this. And we understood that it wasn’t okay, that we couldn’t really do it so openly. And our parents explained this to us. But there was the moment that we disagreed; we were youthful, somewhere so maximalist. And because of this we were in danger. And the next house where russian special services came could be ours.

When the news was talking about the “referendum”, we came to the theatre studio. Then Alla Volodymyrivna said: “We will become russia in a week”. I couldn’t understand what she was saying.

There was the “referendum”, the “green men”, the installation of a monument to a “green man” in the centre of Simfropol, when a girl gave him flowers, a lot of military personnel – in every public transport, for some reason they were around, everywhere. And you just wake up, and all your TV is in russian.

My sister’s memory is also very cool. She says: “I go to get ice cream, pay in hryvnias at the store, and they give me change back in rubles”.

Despite the fact that the searches did not affect us, it was very scary to realize that this could happen any day, or at four in the morning, as they liked to do it.

“I started realizing that if I didn’t go back to acting, I would regret it a lot”

When you live under occupation, you have to be very careful… In Kyiv, you entered and studied at the I. K. Karpenko-Karyi Kyiv National University of Theatre, Cinema and Television. Why did you choose the theatrical niche?

Mom brought my brother to the Svitanok theatre studio because he was very hyperactive at the age of 4. And despite the fact that Alla Volodymyrivna said that he was very young, she still agreed to teach him. I was very quiet as a child. First of all, I only spoke Crimean Tatar. My father’s words were translated for me. By the way, a vivid memory from childhood: my father comes to pick me up from my grandmother’s house, hugs me, lifts me up in his arms, and I start telling him in Crimean Tatar what a beautiful moon has come out in the sky. And he hugs me so tightly, turns to my mother and says: “I never thought I wouldn’t understand my own daughter”. And my mother translated for him what I was saying.

So, my brother went to this studio, and I was very quiet, introverted, very reserved, shy, modest. And next door to Svitanok was the russian-language theatre studio “Fakel”. That day it was closed and my mother sent my brother to the Ukrainian-language Svitanok.

One day, there was no one to leave me with, so my mother and I came to this studio for a parent-teacher meeting. I was sitting under a chair and Alla Volodymyrivna said: “Bring me this girl”. Mom said I wouldn’t speak, wouldn’t understand anything, and was generally very shy, but she brought me. I sat under the chair for about a month, and then I spoke. And they started telling my mother in the kindergarten that I was starting to open up, to communicate with children. And somehow it went on and on…

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Then, when I moved to Kyiv, this studio still existed in Crimea, but it was under a lot of pressure. They said: “You either switch to a russian studio or leave”. At that time, the teachers had very serious problems, and these were the people who were the first to open Ukrainian classes in Crimea.

And it was because of them that a Ukrainian school was opened somewhere, and they introduced ideas that there should be Ukrainian centres, that Crimea was Ukraine. And when we left, I didn’t study in any studios, I tried to go to the then-famous “House of Pioneers” on Arsenalna area in Kyiv. But I didn’t have time and I didn’t do it.

And somewhere even in the 10th grade, I thought that everyone was so cool, they went to journalism, engineering, but what about me with my acting? And my teachers moved to Kyiv, and I understood that this was fate. And I decided I would try. Then we started preparing with them, with my Allochka Petrova. I was coming to her, we discussed the repertoire, and I began feeling that I was returning to the regime that was in the studio, I began realizing that if I didn’t return to it now, I would regret it very much. And I decided that I would enter the Karpenko-Karyi University for acting.

“We should demonstrate at least a few Crimean Tatar fairy tales for Ukraine”

You are now an actress at the Between Three Columns Theatre. I saw a post on your social media about an ethnic photo shoot, under which you wrote that this was what inspired you to create a lyrical play about Crimea, “Crimean Tatar Tales of Love”. How did this happen?

When I started working organically at the Between Three Columns Theatre, its founder, Dmytro (now my husband), constantly emphasized to me that I was a Crimean Tatar. I told him that I was also Ukrainian, and he said that I was a Tatar by nature.

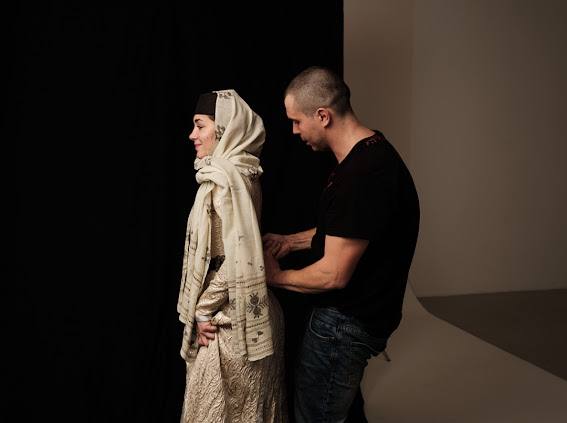

Elina with Dmytro. Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Elina with Dmytro. Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

We were releasing plays, everything was okay. And then my brother gave me a photo shoot for my birthday with a Crimean Tatar named Arslan Ziiatdinov. I looked at his work and told my husband that I wanted something creative like that. He said: “So we need to gather props, costumes. Let’s do an ethnic photo shoot for you”.

We went to the Yar studio in Kyiv. They gave us pots for props. My aunt Maire agreed with Rustem Skybin that he would advise us about these pots and give us the props. Mr. Rustem gave us a beautiful women’s belt, a carpet, and an iron jug. And one day, Aunt Maire started calling her friends in Kyiv asking who could give me a fez (a traditional women’s headdress of the Crimean Tatars in the shape of a truncated cone – ed.).

And it turned around that everyone started helping, completely free of charge. And we come to this photo shoot. Arslan looked at the amount of props, and we also took a huge tabakh (tray), grapes, figs, and pomegranates. Before that, we called Maire, she advised us on what each fruit meant. And the photo shoot lasted an hour and Arslan came in and said: “Oh my God, we won’t have time to photograph all this”.

But this preparation has enchanted me into a costume. How should I wear this, and that, and this? And here we have a busy winter season. And we are undergoing such an organic cleansing of the troupe. Сertain conflicts begun, both among the actors and with the director. Some had many projects, some had personal conflicts, some had lost loved ones, and they followed them. Well, in short, there was a creative mess. And I remember sitting in tears that day and thinking: “My God, how could it be that so many actors have left. Although our season is still going on. We still have a bunch of plays to play. And they are already setting the conditions that we play the last play”.

I then asked Dmytro what we were going to do. I could see that he was emotionally distressed. The next morning, he said: “We’re doing Crimean Tatar fairy tales”. I looked at him like this and said: “What Crimean Tatar fairy tales?”. And he said: “Come on, sit in the kitchen and read me all the fairy tales you have in a row”. I said that I didn’t even know if they existed on the Internet, but I opened a search and started reading these fairy tales to him. And when he heard “Kolobok”, he said, “This is brilliant”. And with tears in his eyes, he said: “We should demonstrate at least a few fairy tales for Ukraine. I’m the same way, I thought that Crimea was an eternal sanatorium where it was easier to get sick than to get well”.

The troupe collapsed, and he said: “We are making Crimean Tatar fairy tales”. And he said that the two of us would make them. And so, we started reading all these fairy tales, preparing a little bit. We just started the rehearsal corridor one after the other.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

We were very worried about how the Crimean Tatars would perceive it. This is a national minority, and it is normal that people, representatives of a national minority, are very picky. I was scared at first. “Crimean Tatar Fairy Tales”. I am a Crimean Tatar, and someone would tell me that it shouldn’t be like this, but it should be another way. And thus, we started consulting with Aunt Maireshka – regarding the costume, how to get around the nuances, whether it was possible for it to have an Eastern association, because we didn’t have a goal of historicity. We wanted to create an association and atmosphere of Crimea. And she began to carefully explain to us what was possible and what was not. Mr. Rustem Skybin advised whether it was possible to use such jugs in the performance or not, whether there would be this association or not.

The first show was fully recorded and sent to Maire for her to watch. And, perhaps, there are some nuances that should not have been shown. We invited Rustem Skybin to the second show.

We were incredibly worried then. Before the performance, we went out to get some fresh air and just then Rustem aga came to the door. He started saying that he was working on his first books. Both religious and the Quran. And when we started listening to him, in terms of how knowledgeable this person was. Not only in ornamentation, in which he was simply a genius. In this sense. The preservation, and the transmission, and what he did. And how much he knew about all this. How much he knew all the nuances, authenticity, traditions, everything else.

And Dmytro says: “Rustem aga, we’re really worried, because we still have a slightly different form”. We adjusted him a little, let’s say. And, as I remember now, Rustem aga, smiled and said: “The theatre always made its own adjustments”.

But after the performance, he wrote to my aunt Maire that it was a very successful performance, and that the form was very well chosen just for the Ukrainian audience – lots of explanations, lots of nuances. And he wrote to me about it, and said that he was delighted, he really liked it. And, when the evaluation was done by people who knew exactly what we should be doing, the tremors started to subside a little, it became a little less anxious, we gained confidence, the performance itself, as they say, started to grow flesh, we started getting a little more oriented in it. And so, it came to life and spread.

“I never liked russia because I knew what deportation was like”

You took a very responsible approach to creating this performance. By the way, I was at one of them in a bookstore, I really liked it, and the first thing I said when I left after the performance was that your children would be very lucky.

I just really want these children to have the opportunity to see Crimea, at least like this.

I remember very well when I came home from kindergarten in tears and asked my mom why everyone had a “mom”, and I didn’t – I only had “ana”. It wasn’t in my awareness that it was the same thing. And until the fifth grade, I was very afraid to call my mom on the phone.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

And one day I called my father on the phone – Dad. Even though my father is Ukrainian, he always heard only the form “baba”. I called him Dad, and as I got into the car, we drove away from the school, he stopped on the side of the road, turned to me, and said: “Don’t you want to explain anything to me? Why did you call me Dad on the phone? You’ve never called me Dad in your life. If I hear you being ashamed to speak Crimean Tatar to me or your mother again, we’ll have a fight”. But I didn’t realize how right he was at the time.

But still, my parents weren’t radical enough in terms of saying that this is Crimean Tatar, that this is Ukrainian, that you have these roots and these roots, that you have nothing russian. That moment. I never liked russia because I knew what deportation was.

My great-grandmothers survived deportation. One of them liked to talk about it. She liked it when people asked her about it. Another one – never. She always said: “It’s very scary and that’s it”. I understood it myself, but at that time I didn’t understand how it applied to the present. And I started tracing this connection later, when in 2014 another deportation took place, just an unnamed, let’s say, forced eviction and resettlement.

“They have never seen Crimea. Show them Crimea”

How do you feel when people come to see “Crimean Tatar Tales of Love”?

Happiness. Absolutely. Because every time before going on stage, Dmytro and I hold hands and he told me: “They have never seen Crimea. Show them Crimea”.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

And that’s why every time we go out, we show them the Crimea that we want them to remember. Not only Sevastopol, not only the association with the Pushkin Theatre, “Horkyi Street”, but Crimea, as it really once was to us.

It is not the same now, but showing them Crimea is an indescribable happiness, especially when non-Crimean Tatars come. I really love it when Crimean Tatars come, because they understand a lot of jokes and they really get them. And that’s great. And it’s very valuable when Ukrainians start to take an interest in this, when they react to the fact that Crimea is part of us, that we should be aware and understand what kind of people there are, what kind of culture there is, and what traditions there are.

And magic is only created with the audience, of course. Because when we were preparing this performance, we didn’t think it would turn out so funny. We proofread this material, yes, but when the viewer came in, the viewer began to find own meaning in it, to react to certain things in own way.

Every time we ask ourselves the question: what will we play about today, what kind of Crimea will we show today? And some news appears about arrests in Crimea and you are starting to resist. And there are performances that are so emotionally intense that I can burst into tears in the middle, holding myself back as much as possible.

“A theatre in which meanings prevail over scenery”

Yes, it has already grown into a certain mission – to spread and popularize our culture among our own people.

We position ourselves as, first and foremost, an educational theatre. A theatre in which meanings prevail over scenery.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

I mean, we are trying to open up new knowledge to people about where they live. Because this ignorance breeds indifference. In order to love this land, one shall understand why they should love it.

That’s why education is a global goal. There is a new generation now, and there are many who still glorify Tsoi, whom they never even saw. And it’s very scary. Because my children will live in the environment that will be formed around them. And that’s why, in preparing for children, it’s very important to prepare the environment for these children.

At the end of the performance, Dmytro gave a closing speech about Crimea and its de-occupation. He could barely hold back his tears. Why was this such a painful topic for him?

First, he is very hurt by the fact that he never knew that Eastern wisdom was not only Omar Khayyam, he never knew that Crimea was not only a black doctor.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

And there is an inner desire to see the Peninsula through my eyes, through the eyes of the Crimean Tatars, who have a culture there. And the desire for children to see Crimea. Of course, the fact that we are a couple influences him. He realizes that this is a very painful wound for me. But he wanted to create this, which is a certain compensation in terms of the fact that he didn’t recognize this Crimea then. He didn’t see it. And he really wanted others to have this opportunity.

Maybe not even the children, maybe the grandchildren. But it’s partly his own pain that he was in Crimea very often, but didn’t have this awareness that it was a different culture, different people there, why did the Azan (call to prayer – ed.) sound, what was it, why did it suddenly sound from the mosque to the whole city?

“This is a dream. We don’t know if it will ever come true, because it only happens in fairy tales”

What are you dreaming about now?

About victory. I just want people from Donetsk to be able to go to their Donetsk, people from Crimea to their Crimea, people from Mariupol to their Mariupol. I want all the occupied territories to return to Ukraine.

I don’t know how that’s possible, I’m not a political scientist. I do exactly as much as… No, I don’t do enough, but I do something from my bell tower. I don’t know much about it. But it seems to me that even these fairy tales are a small push towards Crimea. It seems to me that “Maklena Hrasa” is a small push towards national consciousness. It seems to me that the play “Zhadaika” is an impetus for Ukrainians to survive in 2022 not through fear, but through strength and will. Because they transformed this fear into this.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Photo provided by Elina Khodakivska.

Of course, I want to see it, I want to restore it. But I understand that it is a very big job, a lot of work needs to be done, a lot of donation to be made, an incredible amount of reading and realizing who you are, and learning history. We need to help the army a lot, psychologically and materially, we need to volunteer. We need to do a lot for culture: open up new frontiers, not be afraid of judgment, and try. Let there be so much of it that we can choose. And the dream is absolute peace with all territories.

This is a dream. We don’t know if it will ever come true, because it only happens in fairy tales.