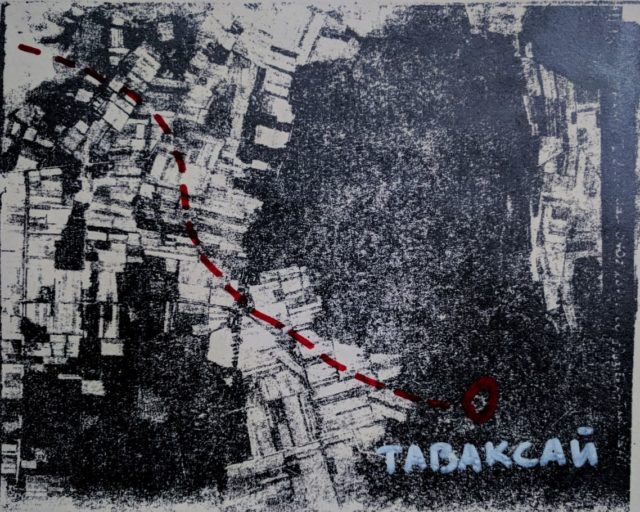

Hell road. Tashke — Tavaksay

19 days and nights,

3500 kilometers of unimaginable suffering

Diary of Nariman Kazenbash

19 days and nights,

3500 kilometers of unimaginable suffering

Diary of Nariman Kazenbash

This book captures memories of Nariman Kazenbash, a Crimean Tatar boy who endured the forced deportation from his native Crimea in 1944 with thousands of other Crimean Tatar people. The original diary that little Nariman kept during the entire journey into the unknown, unfortunately didn’t survive.

Nariman was able to re-create it as an adult from his memory. The book you are holding in your hands now is that diary.

Before you open this diary, we recommend learning more about the history of the deportation of the Crimean Tatar people that was memorialized by Nariman Kazenbash. This will allow you to better understand the context and meaning of his memories reflected in this book. We put together a brief overview of these historic events below.

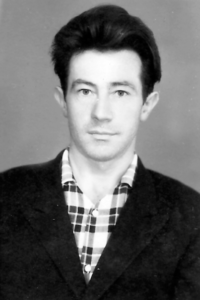

Author’s Biography

Nariman Osman oğlu Kazenbash (1930 – 2016) was born in Simferopol, also known as Aqmescit, the second-largest city on the Crimean Peninsula. During WWII as a teenager, he joined the anti-Nazi resistance movement where he served as a scout.

After surviving a harrowing journey of forced deportation with his mother and sister, Nariman landed in a remote village in Uzbekistan. While his father fought Nazis during WWII, his family was forced to start a new life in Uzbekistan after losing all of their possessions.

After the war, Nariman aspired to get an education and work in the metrology field but faced discrimination because of his ethnic background. After finishing the 8th grade, he was accepted into the mechanical engineering department of the Chirchik Technical School, but because of his “unfavorable” ethnic background, he was transferred to a less prestigious construction department. He refused to comply and left the school. Nariman ended up working at a factory, while taking an active part in its social life, where he played the violin and mandolin, eventually applying to acting school.

Nariman persevered with his original dream and continued to work in the construction of electrical grid systems, working his way up from foreman to the head of the production and technical department. He was eventually accepted at the Mendeleev Research Institute of Metrology.

Later Nariman Kazenbash became an activist in the Crimean Tatar national movement. He was a well-known member of his community as a long-term leader of the Association of Crimean Tatars — Veterans of War and Labor.

Nariman Kazenbash died in Crimea in 2016 and his legacy continues to live through the impact he had on the people who knew him, as well as the memories that he captured in this diary.

Honors received by Nariman Osman oğlu Kazenbash:

1. Cavalier of the Order of Merit, III degree

2. Cavalier of the Order “For Courage”, III degree

3. Cavalier of the Order of the Patriotic War, II degree

4. Jubilee medal “60 years of liberation of Ukraine from fascist invaders”

5. Medal “15 years of the Armed Forces of Ukraine”

6. Order of the Patriotic War, II degree

7. Medal “For Courage”

8. Jubilee medal “60 years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945”

9. Jubilee medal “65 years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945”

10. “Veteran of Labor” medal

Historical background

Forced expulsions of Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars (or Qirimli) are an indigenous people of Ukraine of Turkic origin, formed on the Crimean Peninsula and in the steppes of Ukraine.

In the course of their history, the Crimean Tatar people survived three waves of forced expulsions. The first time — in 1783, when the Crimean Khanate was annexed by the Russian Empire. As a result, many Crimean Tatars left for the Ottoman Empire in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

For the second time, the Crimean Tatars survived the unlawful deportation of 1944, which was perpetrated by the Soviet authorities. Starting in the early hours of May 18th, 1944, and over the course of the next several weeks, over 191,000 innocent people were deported to Central Asia and other northeastern regions of Russia. Today we can estimate based on several sources that between a third to almost a half of the Crimean Tatar population of Crimea died as a result of these atrocities.

Returning home from their forced exile after Ukraine gained its independence in the 1990s, many Crimean Tatars were forced to leave their homeland again in 2014 after Russia’s unlawful military invasion of Crimea.

Forced Deportation of 1944

Nariman Kazenbash and his mother were swept up by the second wave of forced deportation in 1944.

The forced deportation of the Crimean Tatars in 1944 is one of the most heinous examples of the mass crimes committed by the Soviet government during the Second World War. The official excuse for these atrocities rested on the false accusation against the entire Crimean Tatar people of collaboration with the occupying Nazi authorities.

The real reason for the forced deportation of the Crimean Tatar people lies in the nature, ideology, and genocidal practices of the Stalinist regime. Since the mid-1930s, Stalin and the enforcement authorities harbored deep distrust in the ethnic minorities inhabiting the borderlands of the USSR. In particular, towards the Crimean Tatars who lived near Turkey.

The deportation process began at dawn on May 18. The NKVD enforcers entered the homes of the Crimean Tatars and gave them a few minutes to gather their belongings, some only managed to grab their papers.

Approximately 191,000 Crimean Tatars were deported from their homeland. Most of them were deported to Uzbekistan (151,136 people) and adjacent regions of Kazakhstan (4,286 people) and Tajikistan while smaller groups were sent to the Mari ASSR (8,597 people), the Southern Urals and the Kostroma region.

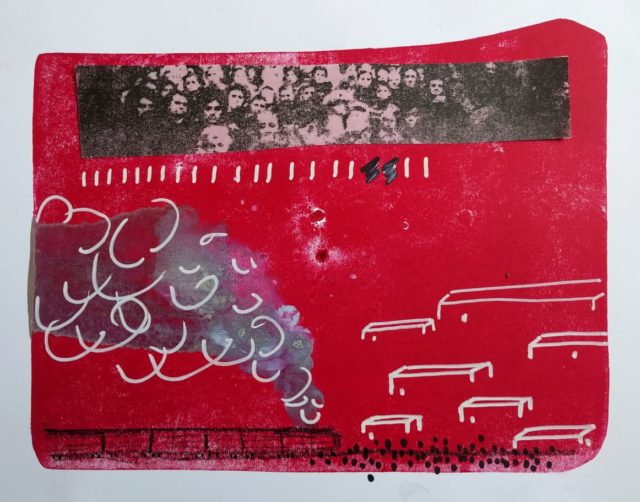

The deportation process itself was inhumane. People — adults, children, the sick, the elderly — were placed in cattle cars that were not fit for human transport. People endured long weeks of the journey under armed guard, without adequate food and water. By the time they reached their destinations on June 4, 1944, thousands of people perished in these unbearable conditions.

According to estimates by Crimean Tatars and activists of the Crimean Tatar national movement, about 46% of those who were deported died in the first years of exile. Researchers in the Demographics and Social Research Institute of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine estimated that 49,200 Crimean Tatars died in camps or so-called special settlements. Determining the real scale of these fatalities would require access to the archives of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and the Russian Federation, which is unlikely to be granted in the foreseeable future.

The vast majority of Crimean Tatars were re-settled into these so-called special settlements — areas surrounded by military guards, checkpoints, and barbed wire fences, which looked like labor camps rather than peaceful settlements.

The crime of the Soviet authorities led to the destruction of the traditional way of life of the Crimean Tatars. While they traditionally engaged in horticulture, growing tobacco and viticulture in Crimea, in exile they were forced to labor in logging, mining, and construction of hydroelectric power plants.

After they expelled the Crimean Tatar people, the Soviet authorities proceeded to extinguish all memories of them from Crimea. They seized Crimean Tatar’s homes, livestock, and cultural and historical heirlooms. According to the UN Security Council’s 1973 report, Crimean Tatar people lost 25 million books, libraries of hundreds of Crimean Tatar schools, etc. The Soviet authorities also destroyed the few mosques that managed to survive the Nazi occupation. Religious traditions, such as wedding ceremonies could only be preserved within families, away from the watchful eyes of the authorities. Most notably, the Soviet authorities purged Crimean Tatar toponyms — the names of streets, cities, towns, villages, and geographic features, like mountains and rivers – completely erasing the evidence of existence of Crimean Tatars in Crimea.

Soviet authorities didn’t stop with the cultural erasure of Crimean Tatars. Soon after the forced deportation, they began the process of re-population of Crimea. On July 14, 1944, Soviet authorities moved 51,000 people, primarily ethnic Russians, into Crimea. The new settlers were allowed to take over the homes of the newly dispossessed Crimean Tatars. This is a standard practice of Russia in its wars of conquest; to replace the native population with ethnic Russians to gain a foothold on the occupied land.

In 1948, Moscow issued orders to permanently exile Crimean Tatar people. Those who travelled outside of the special settlement areas without special permission from NKVD, risked 20-year jail sentences. In time, the Crimean Tatars fought to expand their rights. However, though the formal ban ended, functionally the ban remained in place and Crimean Tartars were prevented from returning to Crimea until 1989.

In 2015, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine recognized the deportation of the Crimean Tatar people in 1944 as an act of genocide. May 18 is recognized as the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Genocide of the Crimean Tatar People.

The Myth of Russian Crimea

Russia continues to spread propaganda narratives about historically Russian Crimea. Countless historians from around the world offer evidence to the contrary.

The written evidence of the history of Crimea spans millennia, during which various tribes such as Scythians, Greeks, Cimmerians, Romans, Bulgarians, Goths, Huns, Genoese, Tauri, Kipchaks, Khazars and others lived here, while the Crimean Khanate and the Ottoman Protectorate ruled the peninsula.

We offer you an excerpt from the text of the historian, a native of Crimea, Serhii Hromenko. The passage is taken from the Y. Hrytsak’s book “Re-Vision of history. Russian historical propaganda and Ukraine”:

Contrary to widespread myths, neither Crimea as a whole, nor any part of it, ever belonged to Rus’. Therefore, it makes no sense to seek any foundations here for the idea that Crimea “always” belonged to Russia. The Crimean Khanate was dismantled only in Spring 1783, and St-Petersburg annexed its territory, after which the peninsula remained in the Russian Empire for 134 years, until spring 1917. Then, during the 1917–1920 revolutionary mess, Crimea was controlled by various “Red” and “White” Russian governments. From Spring 1918 to Autumn 1919, Crimea was occupied by German or French armies. Then, for the next 34 years, until 1954, Crimea became a part of Soviet Russia, with a break for German occupation which lasted from Autumn 1941 to Spring 1944.

Hence, Petersburg and Moscow together possessed Crimea in total from1783 to1954, i.e. 171 years but, actually, taking into account the period of occupation, this period was 3.5 years shorter. Therefore, out of 3,000 years Crimea’s written history (9th century B.C. – 21th century), it was part of Russia for only 168 years, which accounts for 5.6% of Crimean written history.

Content of the diary

3. A few words about our family

6. The first assignment

6. Journey to Taman

7. Unexpected encounters

9. Afterword to the “Encounters”

9. Under Alushta police surveillance

10. “Volunteers”: how it happened

13. Hell Road

39. Meanwhile on the frontlines…

40. Heroes

43. Acknowledgement

43. Search protocol (text copy)

A few words about our family

My father, Osman Dzhafer oğlu Kazenbash, was born in 1907 in Alushta. He was a veteran of three wars: the unfathomable and bloody Finnish campaign [1], the terrible war with Nazi Germany and a brief war with Japan. He earned the rank of Guard Major. At the time of the deportation of the entire Crimean Tatar people and our family as part of it, he was fighting against the Nazis. His war journey went through Poland, Hungary, and Austria. He took part in the storming and capture of Berlin.

After demobilization in 1946 he returned to Simferopol in hopes of joining his family. Only then he learned from his fellow soldiers and pre-war colleagues from the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the horrible fate that befell the Crimean Tatar people.

Perhaps the most trusted amongst them, racked with guilt, talked about the return of the mostly officers and senior staff who fought against the German military machine, Crimean Tatars among them, and demanded the return of their forcibly displaced families back to Crimea. About 15 to 20 of them were talked into getting on a bus (back then called a “box”) under various pretenses and driven into an unknown direction.

Several decades later in the 1970s, after the return of a small contingent of our people to Crimea, we managed to learn more about what happened.

The bus driver, an ethnic Russian, a former war veteran himself, and a native of Karasubazar supposedly fell ill and took a sick leave. A different driver was put behind the wheel and several policemen were sent to accompany them. The fate of this group of veterans, policemen, and the bus driver was shrouded in mystery.

Some years later we heard that some boys found fragments of a bus in the Karasubazar area — a steering wheel, metal parts of wheels (discs), and three rusty pistols.

Jumping ahead, I recall one more episode. In 1975, my late father (Allah rest his soul in peace) and I found the intended bus driver, who was now an old man. He told us this story and tearfully begged us not to come to him again and not to ask any more questions. He added that he would have to leave Crimea. “They won’t let me live here anyway…” he said.

Returning to 1946. My father learned from friends that we were in exile (in Tashkent, Uzbekistan). As soon as he arrived, as a Guard Major, he immediately reported to the military commandant’s office in Tashkent, where he was greeted as a returning veteran in a victorious war. His paperwork was marked accordingly, and he was instructed to report to the special commandant’s office at his family’s place of residence. When asked what for, he was told that he would learn everything he needed to know at that office.

The following day my father went to the special commandant’s office that supervised the exiled (repressed) Crimean people. A senior lieutenant, “the commandant himself”, met with him and demanded that he surrender all of his military papers, including awards and decorations. Surprised, my father asked for an explanation. The commandant’s rude, insult-laden response was that it had to be done that way.

My father asked to see the written justification for such treatment. In short, an impartial exchange between a “rear echelon rat” and a veteran of three wars took place. It ended with my father surrendering his papers, supposedly for verification. He was given a confirmation slip and was ordered to return in three days’ time.

When he arrived at the appointed time and asked for the return of the papers and his presentation pistol that was given to him as a commendation from the Army Commander for his service, he was arrested on the trumped-up charges of “insulting the Commandant and resisting the authorities”.

My father spent six months in the Tashkent [2] prison. Upon his release, he was issued a certificate with the right to receive temporary identity papers and, in the future, a passport. His refusal to endure the humiliating monthly registration procedure that involved showing up and signing to confirm that he did not run away, cost him six months in the infamous “Tashtyurma” (Tashkent prison).

…There was another old story in our family. The last Russian emperor Nicholas II, who came to be the last of the Romanov dynasty rulers, used to vacation in Crimea. During each visit the palace invited my k’artbaba (maternal grandfather) to Livadia [3] to create flower arrangements from beautiful roses that he grew in his garden; arrangements for various events: diplomatic receptions, family and religious holidays, other celebrations.

From my mother’s stories I learned that of all these festive occasions, the most challenging for k’artbaba were the creations he made for birthday celebrations. He had to consider the room where the celebration was taking place, what kind of light, ceiling height, colors, and textures of its walls. He had to know the eye and hair colors, the attire, as well as the age of the person who was being celebrated.

On such occasions, the emperor presented my grandfather to his guests at the beginning of these celebrations as a great original artist, a kind man, a friend of the family, taking care to properly pronounce his given and family names, introducing him as one of Crimea’s indigenous people — a Crimean Tatar.

K’artbaba’s efforts were generously rewarded. The tsar’s [4] wife would settle his accounts upon the completion of each event by inviting my grandfather to a separate salon. A pair of mounted gendarmes escorted k’artbaba to the Angar overpass, unless it was after the nightfall, in which case they would escort him to his residence. The reason for such measures was that the Angar overpass was known for the occasional ambushes.

I recalled k’artbaba stories many years later, when the matter of the return to our native Crimea from Sochi, my rahmetli (dearly departed) mother put forward one condition at the family meeting; to spend the rest of her life where it had begun — either in Alushta, the homeland of my father and my wife, Fevziie, or in Simferopol, where both my mother and I were born.

In the end, we all agreed to move from Sochi to Simferopol. We considered many options and settled on trading a three-room apartment in a two-level cottage with an orchard of fig, persimmon, hazelnut, feijoa, tangerine, pomegranate, and other prized trees, for a mediocre three-room khrushchevka [5] apartment on Kyivska Street, near the Palace of Trade Unions, where we still live today.

Relatives and friends who’ve seen our home in Sochi were greatly surprised and would ask why I accepted such an unequal trade and if I had any regrets.

I’ve always replied that I am content because, unlike many of my peers and compatriots, I was able to visit the graves of my rahmetli (dearly departed) mother and father and read a prayer.

… Back in 1939, my mother was transferred to work at the Bakhchisaray district party committee to be in charge of the accounting department. My father got transferred as well. In Simferopol he worked in a criminal investigation department. He was transferred to Bakhchysarai to be a passport office administrator.

We were afforded accommodations in the Militia aralığı (Militia alley), now N. Spaï Street, two blocks from the Khan’s Palace [6]. The “October” movie theater was on the corner, which according to my father’s recollections, was the site of a mosque before the revolution. These days the holy site has been rebuilt and is one of the prominent landmarks and a holy place for Muslims.

We were a family of four. Back in the early 1930s, at the time of a famine in Crimea and throughout the USSR, many children were orphaned. At that time, an unofficial suggestion was circulated to the leaders of various departments to adopt at least one child from the overcrowded orphanages.

Our people have a long-standing tradition not to give up our children into institutional care. This is how my sister, Muniver (Ramazanova), came into our lives; her late parents were our distant relatives. In May 2013, she turned 90 years old. That June I was able to visit her in the city of Goryachy Klyuch, in the Krasnodar region. We had much to reminisce about.

The war, or rather the onset of World War II for the Soviet Union, found us in Bakhchysarai. As a military man, my father immediately reported to the army recruitment office, not waiting for his summons. Soon he became one of the defenders of Sevastopol.

In November, when the enemy was near Bakhchysarai, all district committee workers had to go into hiding to set up resistance sites. Even before the arrival of the Nazis, most of the children of the district party committee leaders, and rank and file party members were sent away to live with relatives and other relations in rural areas.

I categorically refused to be sent away and stayed with my mother on the day the district committee workers went into hiding. I remember the panic at the district committee. People were running around, burning papers, talking, and whispering to each other that the Nazis were approaching the railway station.

I was helping my mother pack the typewriter when Vasyl Ilych Chornyi, the second secretary of the district party committee, walked up to us and told my mother: “You are responsible for the typewriter with your head – and, looking in my direction, raised his eyebrows in surprise – And what is this? Why is Narik here? He should be in the village!” Before my mother had a chance to respond — I spoke up daringly: “My mom will carry the typewriter on her shoulders, and I will carry the paper — it is not that heavy”.

Vasyl Ilych laughed. It was the first and only laugh I heard that day. He added: “Load him up with his light paper”. I sat down on a stool and was loaded with a backpack (a sack with strings) with piles of grey, sandy paper. When I stood up, I almost keeled over under the weight of the sack.

There we were, my mother with a typewriter on her shoulders, and me with paper and spare parts for the typewriter — we walked to the resistance base in the woods. When we reached the base and I took the sack off, I felt burning and pain — the strings left bloody marks on my shoulders.

The first assignment

We never had a chance to settle down and set up at this resistance base in the woods — only four days had passed when we came under Nazi mortar fire. In this very first fight, the squad commander, Syzov, was killed. The squad’s commissar, Vasyl Chornyi, replaced him.

After the fight, he gave me my first orders. “They killed our commander. The boys will give you his leather coat. Let the women look at it, wipe the blood stains. Tomorrow you will take this coat to Bakhchysarai, to house number 44 near the railway station. They will know where to send it next”.

Later that night, the women examined the coat, folded it carefully and placed it in a bag, covered it with two pairs of worn women’s shoes and two women’s sweaters (also not new); I threw onions into the corners of the bag, tied the ends with ropes, turning it into a makeshift backpack. At 8 in the morning, I was near the housed number 44 and handed over the coat. They fed me, gave me a glass of milk and a quarter of a flatbread. I thanked them and left. I walked carefully to avoid running into a hazard. The enemy, with German precision, made planned raids at 10:00 in the morning in crowded places: markets, railway station, busy streets, etc.

Two days later Vasyl Ilych thanked me in front of the squad and said that the leather coat was delivered to the address, handed over to the widow of commander Syzov, and that it had already been traded for food, food was running out, people were facing starvation.

I took the shoes and sweaters to the oboz [7], to the custodian, as these items were considered inventory that would be traded for food, so they had to be returned to the storage. I finished the assignment without an official pass, or “ausweis” [8]. The assignment was extremely risky, because both Soviet citizens and the occupiers knew that leather jackets and, even more unmistakable leather coats were worn by the Soviet leadership ranks, and they were all communists.

Later we’ve always had an ausweis, as they were supplied to us by the undercover agents who worked in the city and village administrations. During the occupation, there were a lot of assignments — both on the base and outside the base, undercover. Some of them are seared in my memory forever.

Journey to Taman [9]

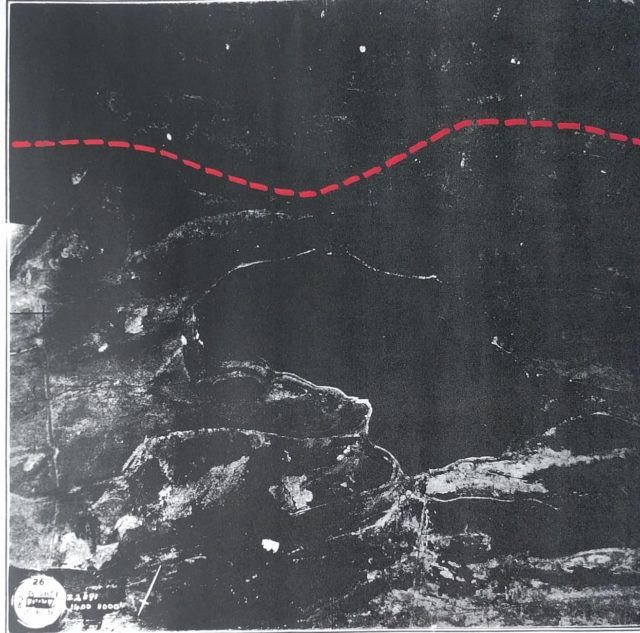

In the first half of January 1942, I was told to report to the staff dugout. That evening, at the appointed time I arrived at the staff location. There were two people present in addition to the commander, Vasyl Ilych: one dressed as a civilian, the other in an officer’s uniform. The officer put two maps in front of me on the table — a real one and a contour map (where objects are unnamed — only dashes on a white sheet of paper).

The officer proceeded to mark dots on both maps in several spots. Then the real map was removed, and I was asked to mark these dots on the contour map.

They repeated this several times in the course of an hour, including two or three smoking breaks. I was puzzled as to the meaning of this game. In the morning, they tested me again. The officer who tested me concluded that I had an excellent visual memory.

On that same day, in a company of guides, we went to a place near Balaklava where the Germans and Romanians were gathering troops and equipment. My task was specific — to count the approximate number of horses with large hooves, weapons with small and large caliber barrels, barracks for soldiers in mouse-grey overcoats (Germans) and yellow-marsh ones (Romanians). Later I had to explain it in layman’s terms.

After my report to the staff, they spent time working out some calculations, then argued about something, interviewed me again and finally, on the third day they once again tested my visual memory on the contour map. I picked up my backpack, put trading items in it (that was my “cover”), and at night I was taken from Kerch to Taman. A “beacon” would be ignited periodically from Taman for me to keep me from losing direction.

On the mainland, I was greeted, praised, fed, and given a hot herbal tea. While I was having tea, the staff officers unfolded the same type of maps in front of me and I pointed with my finger the dots that I remembered. I was told to sleep until the evening and, when it got dark, they walked me back. I got lost for a bit on my way back. Since the searchlights were constantly lighting up, I was forced to stop and freeze a few times. Because of these forced stops, I was off course by a few hundred meters, so it took me another 15-20 minutes to find my handlers. I was told beforehand that in case things went wrong, I should be searching for my handlers as they would not be searching for me. The exact opposite was in Taman.

When I returned to the squad, Vasyl Ilych ordered me to rest. The following day at 15:00 he came and said: “Things will start happening now and tomorrow you will go to the same spot where you were before the journey to Taman and see what they have accomplished”.

It started at exactly at 16:00 according to Vasyl Ilych’s watch (he had a compass watch with a huge dial). The sound rumbled near Sevastopol – Balaklava and spread to us in the woods. It was terrifying — from that shore and from the air. It seemed that shells and bombs were exploding nearby, that stones, earth, and trees would be falling. We would huddle, instinctively look for shelter, even though nothing threatened us directly.

The following day, my friend Vovka and I — his mother also worked in the district committee, and he also refused to be sent away to a village — went to the familiar spot. We saw a terrible spectacle: ruins and craters where the barracks stood before. Both the Germans and the Romanians were still carrying out the dead (the wounded must have been taken away earlier). Dead horses, broken cannons and other chaos remained.

We pretended to collect shell casings and other useless things, while the Nazis did not pay much attention to us, or they did not care about us. We tried to stay out of trouble and keep our distance, while observing and remembering the general picture. Overall, this entire sector marked 16 (1942) resembled a huge dead space, some unimaginable dump. We returned to the base and reported everything.

Three days later at the line-up the commander recognized me on his own behalf and on behalf of the command of the Red Army’s Taman wing. He said that as a result of this operation, a large concentration of enemy troops was destroyed and the carefully planned Nazi offensive was thwarted.

And the radio comms operator Amidov secretly told my mother that my surname was the first on the list for the commendation in the message he transmitted to the mainland.

Unexpected encounters

On another occasion, in early 1942 I was ordered to report to the staff dugout. Once again at the appointed time in the evening I showed up at the staff location. Squad commander Vasyl Chornyi was there with two others. One of them dressed as a civilian, the other in a Red Army officer’s uniform.

The officer put two maps in front of me on the table — a real one and a contour map (no toponyms — only dashes on a white sheet of paper). He marked several points on both maps with lentils and told me to memorize them. Next, he removed the real map and asked me to mark the points that I remembered on the contour map. They repeated this exercise several times in the course of an hour. As the staff members would go out to smoke, I remember thinking what is the meaning of this game?

In the morning I was tested again. The officer who tested me concluded that I had an excellent visual memory. I received all the instructions on how to act in different unforeseen circumstances.

On the same day the guides showed me the way, and I found myself not far from Balaklava, where the Germans and Romanians were gathering troops and equipment. My task was “simply” to remember everything down to the smallest detail: approximately how many horses with large hooves (draft horses), how many weapons with small and large caliber barrels (everything was disguised, but the ends of the barrels were visible). I had to find out how many barracks there were for soldiers in mouse-grey overcoats (Germans) and how many for soldiers in yellow-marsh ones (Romanians).

My late mother recalled that additional scouts were dispatched, and they confirmed my observations. Only after that a chart was drawn up capturing the concentration of enemy troops.

After receiving my report, the staff members kept calculating something for a while. They argued, then interviewed me again, and checked my visual memory on the contour map on the third day.

In the morning, I picked up my backpack, loaded it with the trading items (this was my “cover”) and that’s it. I had no papers except for “ausweis” (pass), everything had to be committed to memory.

This time according to my orders, I had to reach Karasuvbazar. I will not go into great detail on what this journey was like, suffice to say that it was very difficult. Regular transport did not run of course. It was necessary to bypass patrols, crowded places, possible traps. At the same time, it was important to arrive on time.

I found the meeting place quickly. I walked through the alleys twice back and forth. I studied the area thoroughly (as instructed by the officer in the staff dugout). There were few people here and there, I saw one guy twice; the first time he was walking with a girl, and the second time, returning alone.

When I ran into him the second time, he first walked past me, then turned around and questioned what I was doing there. I replied calmly that I had a sick sister, and I was looking to trade some of her things for corn or wheat flour to make some bread to feed her.

He looked me over from head to toe, then pointed to a home with a wooden gate and a side door and said that a değirmenci (miller) lived there — maybe he could help with something.

His exact words were: he may be able to help you. He also entered the yard and invited me in, warning that the dog was tied up, and then left without saying goodbye.

At the entrance to the house, I was met by a girl who I saw walking with the guy before. She said her name was Amide, and that she is the miller’s daughter. Overall, our trade was favorable, I was given about three kilograms of corn and about two kilograms of wheat flour. And they didn’t even look at the sweater. They said: you might need to trade it again in the future.

I was treated to k’atlama (flatbread), and then the miller told Amide to walk me to the corner. Before reaching the corner, Amide advised me to go into the yard of the house with a tall fence. From the start, when I explored the area entries and exist, I noticed the tall fence and the wrought-iron gates. Amide said: “Come in, don’t be afraid, the dog is tied-up here”. She said goodbye and left, wishing me a successful trade.

I was greeted by a short man with a black beard, who seemed elderly at a first glance. He seemed familiar. He approached me, gave me a hug, and asked: “Tanimadin’mi meni” (“don’t you recognize me”)? “Very well, very well”, – he repeated several times. As it turned out, it was my Feramuz emdzhe (my father’s brother). I haven’t seen him since 1938, when he visited us on a work trip from Sochi, where he had lived since 1927.

He said laughingly that he was on a work trip again, and this time it was very short. Uncle Feramuz motioned to the man who lived in the house, who brought out a contour map — the kind I had seen in the staff dugout. I took lentils out of my pocket used them to mark two points. My uncle studied the map for a while, as if photographing it with his eyes before it was taken away.

I was given a savory pastry for the road. We said our goodbyes and I left. When I reached the corner, I looked around and saw the guy that I’ve met earlier. We waved to each other. I felt that he was watching me from afar all the way until I reached the edge of town. That’s exactly what he had been doing. He didn’t seem to hide it and, for some reason I felt relatively safe.

Afterword to the “Encounters”

Many years have passed. Our family had to urgently leave Uzbekistan to escape the persecution by the Soviet authorities for their active participation in the national movement. Having sold their house for next to nothing in 1967, after long period of displacement, we settled with Feramuz emdzhe, near Sochi in the town of Dagomys. Several other Crimean Tatar families who were also unable to officially settle in our homeland lived there. They arrived here, found work at the Dagomys tea state farm and settled down. At least we were closer to Crimea.

At some point a relative, Nuri Khalilov came to visit one of the families from Central Asia. Having learned that Uncle Feramuz (or people could also call him Fedr, Fedr Zakharovich, Osman) lived there, Nuri ag’a [10] was surprised and overjoyed. He wanted to see Feramuz emdzhe. He said that they had a lot to reminisce about. When we all gathered for coffee (and not just coffee), they would reminisce about our time in the Zuy woods [11].

On the orders from the Krasnodar area resistance and army intelligence, uncle Feramuz was sent to the Zuy underground squad. During this period, the Nazis were scouring the Zuy woods, so the squad took up a fight.

During a break in fighting, Feramuz emdzhe left his hiding spot and ventured out to help a wounded fighter who was about 100 meters away from him. When he returned, he saw one of the fellow fighters, a young boy in his hiding spot. Feramuz asked him to vacate his spot at first, but then feeling sorry for him, said: “We are not so large, there is enough space for both of us”.

When uncle Feramuz had to leave the woods, on his way out he gifted Nuri Khalilov with a trophy machine gun. Only much later, when he left the Zuy woods, our “accidental encounter” took place, which I described earlier.

… In May, on the eve of the Victory Day, tasked by the Sochi City Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union at that time, Feramuz was interviewed for a television broadcast. The “Chornomorska Ozdorovnytsia” newspaper referred to him as a scout and underground resistance fighter. Archival materials described how in broad daylight, under the guise of an ethnic Adygean [12] who was scorned by the Soviet authorities, he infiltrated the reception of the Burgmaster of Krasnodar and, under the threat of blowing himself up in the office, took lists of people who were to be abducted to Nazi Germany, as well as other valuable documents. He revealed a belt with grenades under his sheepskin coat and warned that he was to leave the Burgmaster’s office alive.

I handed over all photographs, documents, and newspaper materials to our national museum. Feramuz emdzhe died at the age of 70. He was buried with full military honors at the Sochi Central Cemetery. He did not like to talk about his exploits. “That was my work, what can I tell about it?” he used to say. These conversations weren’t encouraged in our family. The talk of war, deportation, forced expulsion in 1944 were not mentioned and avoided when possible. No one wanted to open the wounds…

Under Alushta police surveillance

In the spring of 1942, after a series of significant losses, and the guerrilla’s attacks, the Nazis realized that the underground resistance presented a significant threat. The enemy began scouring the woods where the resistance fighters were hiding. This is how we came under mortar fire. We were literally buried under mortar shells. My mother was wounded in the leg, I received a concussion. Food and material storage units (hideouts) were destroyed. We were starving, many had frostbite on their limbs.

There were practically no communications, the radio transmitter was shattered. The command decided that women, children, wounded — should disperse to the villages, settle down with relatives, friends, reliable folks and continue with the underground work. All those who were assigned to groups received the turnout and pass codes. Our group, headed by my mother, had to travel along the Otarchyk – Bakhchysarai – Simferopol – Alushta route.

Khatidzhe apte [13] had her own large family. Her own relatives with children were hiding at her place, and here we were as well. This family would share their last piece of bread with us. Khatidzhe apte used to break the flatbread into four equal parts and feed us along with her children.

We had a few more days to stay. The underground resistance “snail mail” informed us that the Nazis would scour the homes looking for those who were hiding for various reasons, and they would start with the villages that were closest to the woods.

We left Khatidzhe apte’s warm home at 4 o’clock and, as we later learned, the Nazis surrounded the village at 10 o’clock and started entering households.

Had we not left when we did, everyone would have been shot, executed. This is how Nazis punished residents they deemed unreliable. Or they would round everyone up into a barn and burn them alive, as they did in the village of Ulu-Sala. It turned out that we have saved ourselves and Khatidzhe apte’s big family from execution.

After Otarchyk, Bakhchysarai, Simferopol, we finally reached Alushta in the spring of 1942. We went around the villages and distributed leaflets with my sister Muniver and sometimes, with my mother. We had bags on our shoulders, mainly with old clothes and shoes, allegedly to trade for food — bread, potatoes. Sometimes we actually did manage to trade them.

In Alushta, we lived with my father’s relatives on Salhirna Street, building 46. My father, who was wounded near Sevastopol and imprisoned, eventually made his way there. He escaped from captivity with his friend Mykhailo Popov — we called him Uncle Misha.

When he learned where we were, by some miracle my father managed to come to Alushta. He had grown a beard and was hard to recognize. But on the third day he was arrested and sent to the Gestapo prison.

They searched our home but did not find anything. I had 150 leaflets before the search. I managed to twist the whole bundle into a tube, put it in a large jar, wrap it in a piece of parachute silk, and bury it in the yard near the outhouse. After the war, during the exile in Central Asia, we remembered this episode on every Victory Day for our family.

I managed to save the search report, leaflets and the ausweis. I handed over all these documents as artifacts to our Crimean Tatar Art Museum.

My father was imprisoned and tortured for a long time by Gestapo. They found neither “evidence that condemned him” nor the “necessary” witnesses. With the help of the underground resistance agents who worked in the city administration, he was eventually released.

He was given a ‘wolf’s ticket’ [14]. That meant that we were to leave the Alushta area within 24 hours. It was a blessing in disguise. With the help of the underground agents, we were moved to Yevpatoria to report to the local resistance organization.

“Volunteers”: how it happened

The head of the Yevpatoria underground organization at that time was a man named Yeromin or Yeromenko, I don’t remember exactly. I saw him only once and from afar. He was wearing Crimean (Crimean Tatar) traditional attire – kyalpak (a cap) on his head, and charykhi (boots) on his feet.

At his orders, we were transferred to the Tatar village of Tashke. 11 kilometers from Kezlev (Yevpatoria) there was the village of Tashke, populated mostly by ethnic Russians, and on the 12th kilometer from the city — Tatar’s Tashke. There was only one ethnic Russian family, the Ilychenkos — Uncle Yasha’s family.

The underground cell consisted of five families: ours, the Ilychenkos, the blacksmith Abduveli ahai (master), the Ibrahimovs (who’s elder was also the village headman) and the Islamovs.

Someone would visit us twice a month. They would leave a small sack with leaflets and newspapers (mostly “Red Crimea”) in the old cupboard.

We were distributing these leaflets and newspapers as best we could. In turn, we would be collecting various local official publications and storing them back in the sack (newspapers, information leaflets published in Russian and Crimean Tatar languages under the strict control of Nazi censorship). This was our way of ensuring that the underground resistance staff knew what the Nazis were doing on the occupied territories. According to commissar Vasyl Ilych Chornyi, this so-called mailing system in general, and this information we were gathering was of great value when important decisions were made to help in our fight against the occupiers.

I never saw the face of a person who was handling mail. Just once, when he was leaving, I saw his back. Sometimes my mother would put flatbreads in the sack for him.

Resistance and underground fighters caused a lot of trouble for the enemy, so German-Romanian units were recalled from the frontlines to fight them. Eventually, the Nazis announced “voluntary mobilization”; newspapers and leaflets boasted announcements about the formation of a volunteer battalion.

In reality, there were no battalion yet, but the Nazis constantly appealed for collaboration with the locals. Only few people responded to these appeals, — mostly those who were scorned by the Soviet authorities at the end of the 1920s and 1930s. People of different ethnicities were among them, since Crimean Tatars weren’t the only ones who fell under the millstone of Stalin’s repressions. At the same time, many of our people worked in city and village administrations. They helped a great deal by obtaining the passes and delivering important information at the right time.

The Nazis realized that nothing would be achieved with the formation of a volunteer battalion and chose a different path. I will give an example of how it worked in the village of Tashke, which, according to our observations and available information, reflected the general picture for Crimea. Looking ahead, I will say that in that difficult time we managed to alert and save many people from such a “mobilization”.

The Tatar village of Tashke was not much different from other settlements in Yevpatoria region and the entire interior Crimea. It consisted of 46 homes. There was a well at the entrance to the village from the Yevpatoria direction, where a horse walked in circles all day pumping water. Water was poured into wooden drums to be then distributed to meet the needs of people and animals.

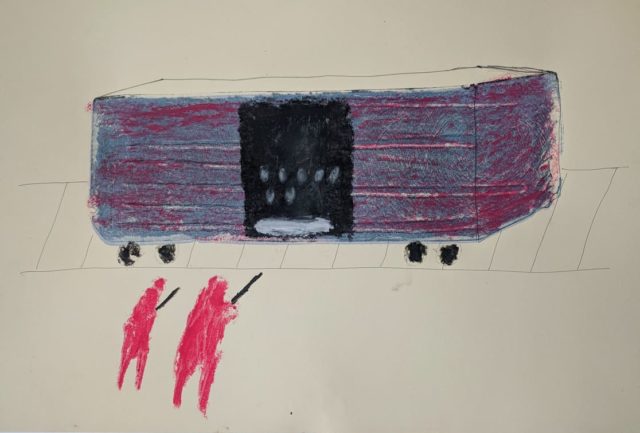

Once, two tarp covered trucks drove up to the well — one with an empty bed, and the other with Nazi soldiers armed with machine guns. They jumped out of the truck and surrounded the village. At that time, 10-15 motorcycles equipped with machine guns drove up. The motorcyclists were stationed between the soldiers with machine guns.

Thus, Tashke was completely surrounded. People were allowed into the village, but no one was allowed to leave. An officer, one of the junior ranks and a paramedic came out of the cabs of the trucks.

Strictly, with German precision, in a staggered order, these three began entering each yard and forcing everyone to exit the house. The order was repeated several times through the loudspeaker in Russian. The goal was to identify men aged approximately 18 to 50.

All those identified were lined up for an examination. The officer would point to a person with a stick, who would then state their name, surname, age. The junior officer was taking notes; the paramedic looked into the mouth, ears, checked the eyes, examined the hands, feet, etc.

After that the men from the village would be loaded into the truck under guard of armed soldiers. From that moment on, any contact with their loved ones was prohibited.

In Yevpatoria, men were housed in long barracks behind barbed wire. After a humiliating anti head lice treatment, their clothes were burned, and they were issued uniforms taken from the dead Nazi soldiers. The uniforms were clean but covered in washed-out bloodstains. People looked ridiculous in these ill-fitting uniforms; the sleeves were either too short or too long, and pants were either too baggy or too tight.

After a month of drills and quarantine, the Nazis used the so-called volunteers to fight against the underground resistance. Before scouring the woods, the Nazis were covering us with mortar fire, followed by the soldiers walking through the woods. In the first ranks, they put the volunteers, local villagers, with old weapons. Sometime later, Romanian soldiers followed, and only after them — the Germans.

Thus, the first to come under the fire of the resistance troops were the “volunteers” walking in first, followed by the Romanians. The Germans protected the “Aryan” soldiers until the last moment of a raid or a battle.

Fellow villagers, friends, relatives “on different sides of the barricade” managed to reach a covert agreement sometime later so when the resistance troops would fire the first salvo into the air, and the supposed volunteers would fall to the ground, leaving the Romanians and Germans unprotected for the next rounds of direct fire.

After such maneuvers, the weapons were taken away from the “volunteers” who remained alive. Instead, they were used in various jobs — from patrolling to building defense structures, digging trenches, etc.

Why am I describing this in such detail? The fact is that this was one of the very important responsibilities of our cell — to painstakingly study the events on the ground, observe everything, talk to people, and provide detailed reports. Vasyl Ilych said that after a minor editing, these reports would be sent to the mainland.

In the meantime, enemy propaganda used newspapers and radio to distribute false reports that a battalion of volunteers had been formed. They even published fake, fabricated photos of people of different ethnicities.

Eventually, when tallying up the interim results of the work of the underground resistance, the staff leadership stated that the plans and actions of the Nazis regarding the organization and use of volunteer battalions had failed. Especially after the so-called volunteers began to replenish the ranks of the resistance fighters in groups and individually.

In the first months of deportation, as a 14-15-year-old boy, I wanted to write about those 19 days and nights spent in a smelly cattle car, as we called it — the death car — which was headed along the Kezlev route. But mother Khatidzhe, Allah rahmet eylesin (may Allah rest her soul), categorically forbade me to do this. It must have been right then, because I wouldn’t have been able to publish my writings anyway. Moreover, I could have endangered the whole family. One could end up being sent to the labor camps for a long time for something like this.

Today, when I am in my 80s, I believe that I simply must do it!

There is one other reason. When I thought about these 19 days and nights, it seemed to me that I would be able to capture everything right away. Since, according to my teachers at school and our commissar Vasyl Ilych Chornyi, ateshi engil olsun (an honorable dearly departed), from the resistance squad, I had a great visual memory.

How wrong I was! It turns out that having a good memory is not enough. One needs to be able to put everything they have experienced on paper. For that I am very grateful to my friend, the editor of our newspaper “Qırım”, Bekir Mamut, who kept asking me to write about those terrible days as I remembered them and, of course, as they really were.

Which I attempted to do. It is a great pity that I could not save that diary, in which I reflected on everything that happened to the smallest details, literally described what was happening in every hour. But some of the records helped me today. Every day of the hellish suffering of those hundreds and thousands of people, entire nations, must be documented, as historians say. In this instance, it is about our indigenous Crimean people…

Before writing about May 18, 1944, I want to remember what happened on the eve of that day. On May 13-14, a military unit was stationed near the well at the entrance to the village. On May 17, around four o’clock in the afternoon, a senior lieutenant and a soldier came to our rundown home in Tashke, both armed with assault rifles. The officer, seeing laundry drying on a rope in the yard, pointed out that it was dry and ready to be folded. He also hinted that mom had done a good job by doing the laundry that day.

We treated them to some coffee that we made from roasted (more like burnt) barley. They had some coffee, thanked us, and left. At five or six in the afternoon, before sundown, the Ilychenkos, husband and wife, our friends from the anti-fascist underground, stopped by. This was the only ethnic Russian family in Tatar Tashke (the village has not survived). Uncle Yasha, as we called him by his conspiratorial name, and his wife brought us half a sack of dry bread and a ready-to-cook chicken. It was an awkward visit. They could not explain the reason for their call or why they brought the food. They said their goodbyes, as if apologizing.

May 18, 1944

On May 18, 1944, at 6 o’clock in the morning, we got a knock on a door. The senior lieutenant, who had visited us the day before, and two soldiers walked in. The officer read us the resolution of the State Defense Committee. He added that he was giving us a separate carriage. “Take all the food you have, bedding and things necessary for the journey. The soldiers and the driver will load whatever you say and want to take”.

I had to help my mother as she was unable to walk by herself. Shortly before the Nazis retreated, she was shot in the leg during one of their raids in the woods. We spent two days laying low in the snow with a group of resistance fighters after that. Many people got frostbite that time.

We had nothing to pack apart from some food and bedding. After asking the senior lieutenant’s permission, I ran to the neighbors to tell them that they could use the rest of the space in our carriage for their belongings. Others in the village were given one carriage for three families. It seemed we were somewhat “privileged” by the authorities.

They were war time combat veteran soldiers. They were clearly holding back. The soldiers would even help when needed. They were used to seeing the enemy in front of them. But here there were women, old people, children, parents of the front-line soldiers like themselves. It seemed that the soldiers did not quite understand why they were there. They were uncomfortable to be “fighting” these frail fellow people.

The soldiers who were rounding people up into the train cars were different, they were the NKVD [15] agents. They must have been convinced that they were seeing only spies and traitors in front of them. They were not just obnoxious, they were rough. I saw some of them swinging their rifles at people. Their angry voices, cursing and profanity laced shouting made me feel a kind of stupor…

They loaded us in quickly — our 15-20 carriages with people and their meagre belongings didn’t take much time. It was obvious that we were not the first to be loaded.

It took us four hours to travel from Yevpatoria to Simferopol. We often stopped and waited for the oncoming empty cargo trains to pass.

There was a rearrangement in Simferopol. Cargo cars were being attached, then detached, pulled back and forth. Finally, we started to move north, in the direction of Dzhankoi, around three o’clock in the afternoon. At first, I counted how many times we stopped, and then I lost track. All the doors were completely shut at the stops. No one was let out. We tried to open the car door just a little to let in light and air, but to no avail. Heavy bent nails wrapped in wire were used as cotter pins that were pushed into the latches that we couldn’t access. In Dzhankoi, we were allowed 10 minutes to stock up on water. Not everyone was able to do it if they didn’t have a suitable container.

While rearangement in Simferopol, I managed to get four burnt bricks from the ruins near the station. Later, we would use them for a makeshift hearth. During the entire 19 days of the journey, families would take turns setting up a fire and cooking, when it was allowed. We often had to hurry to keep up with the train. Often, we had to grab the half-cooked food, burning our hands.

No one slept the first night. Adults talked all night. They were asking the same questions: where they are taking us, for how long we will be on the way, would there be any water and food, how to deal with the sick. There were two gravely ill elderly women and one old man in the car. There were also two young mothers and one pregnant lady. But who among us, victims of criminal despotism, could answer these life-altering and fatal questions in those days?

There were 64 adults and 18 children in the car. On the first day, us boys set up a makeshift toilet at the behest of the adults, by cutting a hole in the floor with knives in the corner of the car and, having fenced it off place with a sheet. Later, the sheet had to be removed in order to wrap one of the deceased, and some nondescript rag was draped instead. People somehow got used to each other and to the awful conditions. And the darkness of the car made the sheet more necessary in the sacred purpose of burying the dead.

May 19, 1944

Early in the morning, the door of the car was pushed open by the guards, — a soldier and an officer. They gave two sheets of paper, a chemical pencil and told us to make a list of everyone present. We asked the officer to leave the door open because it was dark in the car. In the corners there were four windows with bars on them that were approximately 50 by 30 centimeters. While the soldiers were talking to the people, I asked for permission to relieve myself pretending that I could not bear to wait. My trick worked. During this time, I counted how many cars there were. There were 41 in total. In the head of the train, there was teplushka [16], a warm sleeping car for the guards. Our car was the seventh. The cars alternated: one with an open hall where a guard was stationed, the other without a hall, i.e. without a guard. Guards changed every 12 hours. That made it was difficult to get to know them. We managed it, eventually.

On May 19, following orders, we elected something like a car council: my mother was the lead, me and two younger boys by a year were the scribes [17]. The list was ready within an hour, but it remained unclaimed for a while.

Our hopes were dashed. We’d hoped that once they have the lists, they would give us food and water, accordingly, identify the sick and provide them with emergency assistance… We dreamt big. No one came again that day, no one looked inside the cars. The only thing that happened that day was that the car door was shut again when the guards were changing shifts. But before that, I once again managed to count the cars and confirm our placement. It was clearly visible during the turns when you could see all the way from the locomotive to the last car. In the morning, the train stopped somewhere in the steppe. There was a semaphore [18] in the distance, and that meant we not far from some town.

One of the boys happened to have a piece of chalk. So, the entire area of the car was provisionally divided into rectangular sections — depending on how many people were in each family. Two windows with bars were responsible by us boys, and there was no access to the other two, because the floors were missing.

The night of May 20 was restless. Children were crying, the sick and the elderly were lamenting their fate, in their delirium, asking Allah for help. Needless to say, it was an enormous stress, a deep and powerful shock. Consciousness refused to rationally perceive what has happened.

May 20, 1944

The day began with the arrival of an officer, a soldier and an elderly female paramedic who asked if there were any sick people. They wrote down what they were told and left, leaving the hope that our treatment would improve.

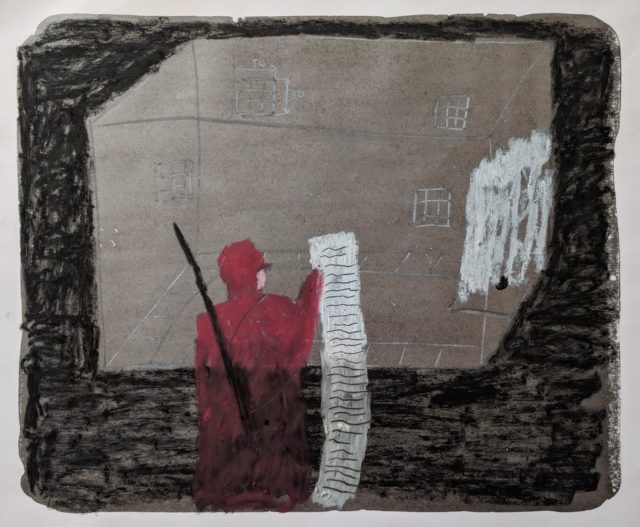

My mother (rahmetli anam) (my late mother) showed me several sheets of blank paper and quietly asked me to collect a few more sheets from my neighbors in the car, sew them together and start keeping a diary of sorts. I was able to find them because the notebooks were considered valuable, and many people packed the paper.

I started writing down the most important events of the day, to the smallest detail, in some ways this looked childish. In addition, I made notches every day on the inner wooden post of the door frame with my folding knife, which I treasured. I ended up making 19 notches. This meant 19 days of a horrific journey, which in our case turned out to be the road to Central Asia.

The whole day was spent waiting for food and water. But the night came, and nothing happened. After the morning visit of the officer and paramedic, the door remained shut the entire time. We ate what we managed to take with us. People did not know how long the road would take, so they treated their meagre food reserve very carefully, rationing it to the extreme. The children were half-starved, not to mention the adults… Another nightmarish night has finally passed. The next morning arrived.

May 21, 1944

We stopped at some small station around six o’clock in the morning. I managed to count four additional railway tracks. Our train was driven into one of the dead ends. Two trains that followed us after a certain period of time came into other dead ends.

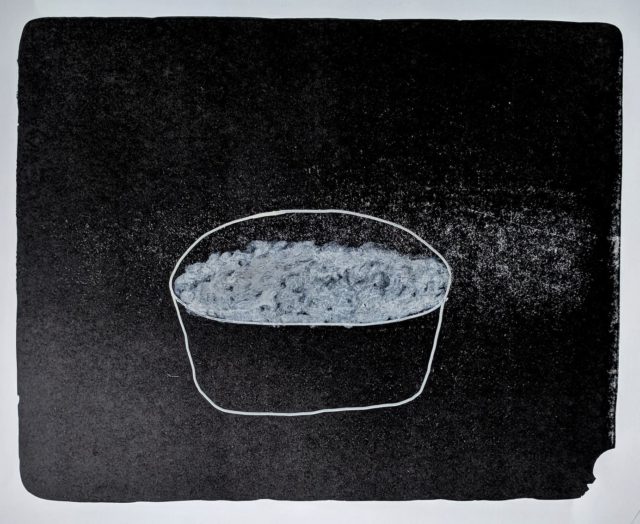

The doors were opened only in our train. They brought us flour soup, some unidentifiable brown liquid in flasks. Feeding that resembled guarding livestock, lasted about an hour. It seemed that when our train was being dispatched, they were provisioned to feed the convicts.

Our train mainly consisted of people from Yevpatoria and several nearby villages. Through the barred window, I managed to find out that the train behind us was carrying the Bakhchysarai residents. That was all I managed to learn.

This night was even worse than the ones before. Hartanai (an old woman), died at dawn. Her stomach swelled. We, teenagers, and children, looked at her stomach with a fear and thought that it was about to explode.

Everyone knew that she had four sons and all of them were fighting the Nazis at that time, and her daughter went to visit her relatives on the eve of the deportation. So, on May 18, there were no adults with the old woman, only two 6-7-year-old grandchildren. Remaining conscious until the last minutes of her life, she asked her countrymen in a quiet voice for one thing — not to leave her grandchildren to fend for themselves and help them find their mother…

May 22, 1944

At about ten in the morning the door was opened by the guards. They asked if there were any dead. We answered yes. The guards told us to leave the corpse on the railway embankment. We followed their orders — we wrapped the old woman in a sheet and sewed it up. The elders read a prayer.

After 20 minutes, the train set off. And while it was gradually gaining speed, I managed to see the similar bundles were left from other cars. I counted 16. Some of the wrapped bodies were children…

In about an hour or a half, we passed a large city without stopping. I couldn’t read the name of the station; the train was moving too fast.

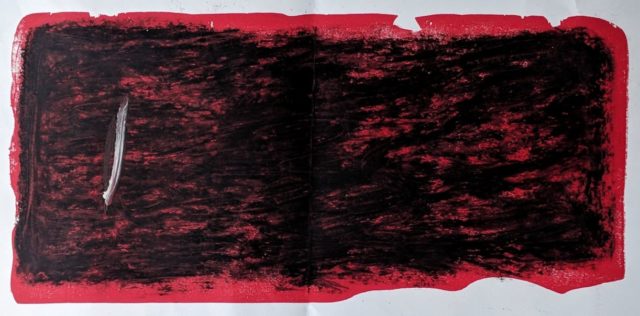

I dreamt about the white bundles along the railway tracks for a long time after. During the day, when we were being taken to the unknown, I looked out the window and imagined this whole long journey by railway, and along it — numerous white bundles of different lengths…

I am now in my 80s and I still have a very clear and distinct memory of that journey to nowhere, especially the white sheets that I saw on May 22, 1944. After that day, I promised myself not to look at this terrible sight. I couldn’t help but witness these again more than once: on May 27 and 30, and on June 1 and 3. But I didn’t fix my gaze on the white bundles, and I definitely didn’t count them.

At the end of the day, the train stopped at a small station. Not even a station, but a halfway stop. The guards opened the doors and said that while the locomotive was being filled with water, and after a sign indicating permission, we could go and collect two large canisters of water for drinking. Henceforth, when this sign was given, we could collect water in those canisters.

In the end we were allowed to collect water once every 3-4 days. During the entire journey, i.e. 19 days, we were offered hot water twice. For the entire journey, flour gruel was distributed four times. Once they gave bread — 5 loaves for the entire car. There was no limit to the generosity and mercy of the authorities…

May 23, 1944

We moved all day without stopping anywhere. We passed some large settlements. Open semaphores flashed; we passed large and then small stations and so on all the way. The train flew past them with a whistle and a noise, without slowing down. Most likely those were the orders. During the night, the train slowed down two or three times, but did not stop.

The most important thought for us was knowledge that we would not be executed. Everything else was secondary. In other words… When water is scarce, when our destination or the reason for being transported is unknown… Our conversations were about the same things. In the evenings, in order not to disturb the others and being somewhat cautious (everyone knew what country they lived in), we spoke in whispers. We did not mention the past life — neither the good nor the bad. All the worry and fears were related to the present and the future …

May 24, 1944

Around 10 o’clock in the morning the train stopped. The guards removed the heavy, loud latches and allowed the carriage doors to be pushed open. The soldiers said that we would stop for about an hour. People were starting campfires. We made as many as two. Some boiled potatoes, and cooked what little food they had.

I managed to get to know and even get close to one of the guards. He said that they were not allowed to communicate with the “passengers”, only in exceptional cases, for example, when they had to pick up a dead.

The soldier’s name was Konstantin. He was originally from Crimea. It was clear that he felt some sympathy towards us. Kostya promised not to lock the cotter pin into the latch of the car door, and he warned us to keep our feet in the car, especially at turns. If a senior officer (the chief of the train), during his regularly inspections would see this, not only he would put an end to such indulgence, but punish everyone, especially the guards.

We promised Kostya to observe all precautions and opened the doors only when the train was moving in a straight line. That’s how, almost the whole day, and even more so at night, we kept the doors open. When Kostya was on duty, and all the way to Tashkent we had the opportunity to breathe fresh air — even this was a gift in those terrible conditions. Fortunately, we were never caught. We were pleased that Kostya was not let down.

May 25, 1944

Two babies died during the night. One of them departed into the light in the evening, while the young mother did not let him out of her hands until the morning. She sat with the lifeless baby the whole night, either not wanting to accept this death, or not hurrying to say goodbye, knowing that she would never see her baby again.

The other baby with an older mother whimpered and cried for a while since evening. The baby fell silent after midnight and died in the morning. Seeing how this baby was being wrapped in cloth, the younger mother stepped forward and gave up the body of her baby…

By the evening, the train started to slow down and stopped at a junction. No one was allowed to leave the cars, but I managed to tell though a gap in the wall to a passing guard about the deaths of two babies. As the train pulled away and began to slowly pick up speed, the guard ran over and said he would leave the door open. He ordered us to wait until it was dark, and when the train would be slowly passing over a long bridge over a large river to throw these two white bundles into the water when he signals.

The young mother, who kept the dead baby close to her chest all night, was mostly silent. Later she was screaming and asking that the baby be returned to her. When the old women (bitaiki) were bundling the bodies of babies in cloth, we guarded the mothers of the dead babies, trying to protect them from seeing it.

When we heard the signal from the hall, we lined up in front of the door, forming a “wall” so that these mothers, as well as the small children, could not see the tiny bodies being thrown from the car into the terrifying darkness. Throwing the bundles with the bodies into the river was not easy. If they didn’t make it into the river, they would have hit the sides of the train and end up laying on the bridge.

The young mother seemed to notice this and longingly cried: “Balamny k’aytarin’iz!” (“Return my baby to me!”). She was screaming something incomprehensible and wailed again. Of course, hearing and seeing this was a shock for us.

In two days, the poor woman was removed from the train. An officer, an elderly female paramedic and a soldier showed up. The paramedic looked at the young mother and said that she should be examined by a specialist. Two days later, at the following stop, I saw the poor woman being taken by the arms to the medical station. In total, three patients from our train were taken there that day. It is unlikely that they were ever to return to their families or countryfolk…

In the car, I’ve heard from the conversations between the old women that the husbands of both women who lost their babies were underground resistance fighters of the Zuy squad during the occupation. And when Crimea was liberated in April, they joined the offensive with the Soviet army and went to fight. In their letters, they wrote that they continued advancing west. Could the Crimean fighters ever imagine what the Soviet authorities, for which they shed blood, did to their wives, children, parents? Maybe only in nightmares — and even then, unlikely…

May 26, 1944

We were on the move all day without stopping. Kind elderly men — k’artbabalar, and gentle elderly women — k’artanalar in light white capes read the prayers for the dead and asked Allah to accept their innocent souls. They also remembered the living, asking for mercy for them.

An elderly man — in a traditional Crimean cap, with a white beard, deep wrinkles, and a particular Kipchak appearance — held the Koran on his lap, but recited prayers by heart. He was mesmerizingly shaking his head, moving his lips, his eyes were closed. I wondered how he could whisper so long without stopping, how much he knew, how he could learn so much.

I thought he could recite the entire Koran. Indeed, he read the holy book for several hours without even turning a page. After repeating the word “Amen!” three times, he would close the Koran on the same page from which he started. All of us would repeat “Amen!” after him. At the end of the day, the train stopped in the steppe. With an unknown settlement seen in the distance – it seemed like a small station. Later we passed through it without stopping. At the next stop, we were told that we would be staying for two hours. Everyone who could started the campfires. Trying to cook something from a meagre food that was saved. Children set up an outhouse under the cars. This, of course, was very different from relieving oneself in a car.

Two hours later the train left. Before leaving, the guards quickly shut all the doors. In the evening, when dusk began to fall, our train passed through a large city at a high speed. The twinkling lights seemed so foreign to me that the usual curiosity in seeing a city in a daylight faded with them. The train plunged back into the darkness of obscurity…

May 27, 1944

One of the sweet elderly men — k’artbaba died this morning. During the last 2-3 days we, like boy scouts in an extreme situation, took turns feeding the old man from a spoon, since he wasn’t able to eat anything at that point.

At noon we stopped at a small station. As usual before reaching the semaphore, where the railway tracks diverged. The doors of all cars would be opened. An officer and two soldiers of the convoy, going to the tail of the train, instructed us: “If there are corpses, put them along the railway track, do not exit the cars”. On the way back, these guards hurried those who had not yet jumped into the car and closed the doors.

We spent the rest of this day, like all previous ones, in a kind of oppressive, mournful silence. Only the faint voice of the white-bearded k`artbabai reciting a prayer to the familiar clatter of wheels could be heard. Even the rowdy boys like us spoke in whispers.

And again, in the blink of an eye, I saw white, grey, and even black bundles along the railway track. The passengers of the ominous train were running out white sheets and swaddling blankets to wrap the bodies of their loved ones.

May 28, 1944

It rained in the evening. The air was fresher. The previous 2-3 days were unusually stuffy for springtime. Being able to open the doors was a break for us. It rained almost all day. The rumble of thunder sometimes resembled a bombardment.

The train slowed down twice but did not stop. In the evening, we found ourselves at a small station. The guards allowed four people from each car to go for some hot water. A bunch of scrawny teenagers, we managed to carry 15 liters. On the way, dragging a half-filled forty-liter canister, we encouraged each other by yelling. Afraid to damage the canister on the sharp stones, we were calling each other weak.

One elderly woman — k’artanai took out some herbs from a paper bag, crushed it with her hands and wrapped it in a gauze. That day we had tea. K’artanai called the tea “chel chai”. I have never drunk such aromatic and pleasant tea before or since. K’artanai, as if to complete her incredibly generous, and under the circumstances almost magical mission, fished out from the depths of her travel sack a glass jar, wrapped in paper, and tied with a thread, and treated the children to a teaspoon of honey. In the following days, until we arrived in Tashkent, we dreamed of the moment when we would be given hot water once again to drink the aromatic tea with honey. The hot and stifling weather only stimulated this simple child’s dream.

May 29, 1944

We rode all night without stopping. We arrived at a large station in the morning. I counted eight tracks. There were trains sitting on some of them – similar to ours, with freight cars. Through the ventilation grates (windows), we started talking with the neighboring car.

The people in that car were from the Fraidorfsky area. Their car was the same size as ours, but initially there 104 of them in it. On the twelfth day, only 81 remained. We were horrified to imagine the cramped and unsanitary conditions they were forced to be in. After all, we all settled around the perimeter of the car, and the middle remained free – if nothing else, at least for air circulation.

It was the worst kind of punishment — to travel for many days without this life-saving sanitary space, a kind of “plaza” in the middle of the car, to travel in a crowded space, like fish in a can. The executioners could let their victims go, as their term had to expire in these life-defying conditions.

But alas! The “most humane” system and regime continued with the genocide of its own people. Later, I met some of the guys from Freidorf in Chirchik and worked with the two of them in the boiler room of the Uzbekkhimmash plant. They remembered the hellish road to exile with genuine horror…

We were allowed to open the doors and told to expect food distribution. There were strict orders to stay inside the cars. They warned us that if someone violated the orders, the doors of that car would be shut and there would be no food for anyone. The same instructions were conveyed to the inmates on the neighboring trains.

Around one o’clock in the afternoon, the gruel, — rough flour cooked in water, was brought in canisters. As tasteless and unpleasant it was, people ate it to give themselves some physical strength, thinking that it was better than nothing. My mother and I also ate it, but with our own dry bread, which we always shared with our nearest neighbors.

May 30, 1944

On this day, the elderly man k`artbabai who recited the Koran by heart passed away. In the morning, we heard him reading the prayer, in an unusual way this time, with frequent pauses, stopping to take a deep breath, then continuing again. His whisper became quieter and quieter.

Later he fell silent. We did not notice right away — we thought that he fell asleep. After 2-3 hours his daughter-in-law said anxiously: “K’ainatam indemei, g`aliba oldi” (“father-in-law is silent, probably departed”). Indeed, he died sitting, leaning against the wall of the car.

That evening we stopped at the junction. His body was left on the slope of the railway tracks. When the lifeless k`artbaba’s body wrapped in a grey cloth, was lowered onto the railway embankment, I couldn’t help but see the countless “bundles” that were lying next to each car.

Grandmothers read the prayer. People were crying because something notable happened that day — we lost not just the eldest among us. We have lost our spiritual father.

K`artbaba’s daughter-in-law, Amide told me later that her father-in-law — grandfather Menumer — had two sons and a son-in-law who were fighting on the frontlines, defending the Motherland. As in every family in our car. And in some families, victory was being forged by two or three family members. They risked their lives defending the very country whose rulers were taking the lives of hundreds of thousands of innocents.

My mother and I were among them… While her husband and my father, Major Osman Kazenbash, shed his blood to free the Motherland from Nazism, his family was being freed from their right to live on their native land. We rode on towards our next trials and torments…

May 31, 1944

I remember that day because my friend Pevzi and I got to wash up for the first time during the entire journey. This is how it happened. Around 11 o’clock we stopped at a small station. The guards said that while the locomotive was being filled with water, we could also replenish our supplies.

When our turn came, we brought out two large canisters. Near the station tap we saw how water was delivered into the tank of the steam locomotive with a “trunk” — a corrugated hose about 10-12 centimeters in diameter. We saw a hose with two taps nearby. We asked an elderly one-armed man who was operating the tap, whether we could rinse each other off. We had not washed or bathed for two weeks, we said.

He said yes. During the watering breaks, when the pressure was strong and the outflow was low, we’d “hide the pebble” to decide who would get to be rinsed off first. “Pokonatysia” is to hide a pebble in one’s hands three times. Whoever guessed correctly more times, won. Pevzi won, so I was going to go last.

We stripped down to our underwear and rinsed off. The one-armed man, seeing how muddy the water was running off our bodies, gave us some much-needed soap. Probably to reward us for our courage and our wish to be clean. When we got back into the train car, everyone in it started laughing, for the first time in our fourteen-day journey. Pevzi and I looked at each other, embarrassed, we were not understanding why our “companions” were laughing.

When an elderly woman — bitai, one of those who usually read the prayers, said “anava Narikkye k’aran’iz, byem-beyaz boldy. Juvinip keldi. Wai, mashala! Mashala! Savlyk’ suvlar bolsyn!..” (“Look at Narik, how clean he is now — he bathed. Well done, well done! Enjoy your bath in good health!”).

June 1, 1944

The day before one of the bitai women became ill. She had trouble breathing. After some discussion, we decided to carry her to our shelf. We placed her near the window. As I later found out, she was born in 1866 in the village of Aidargazi, and was married to a man from the village of Tashke.

Her parents had means before the collectivization [19]. During the collectivization, her almost 90 years old parents, were sent away into the unknown. She was left alone only because her husband was considered poor.